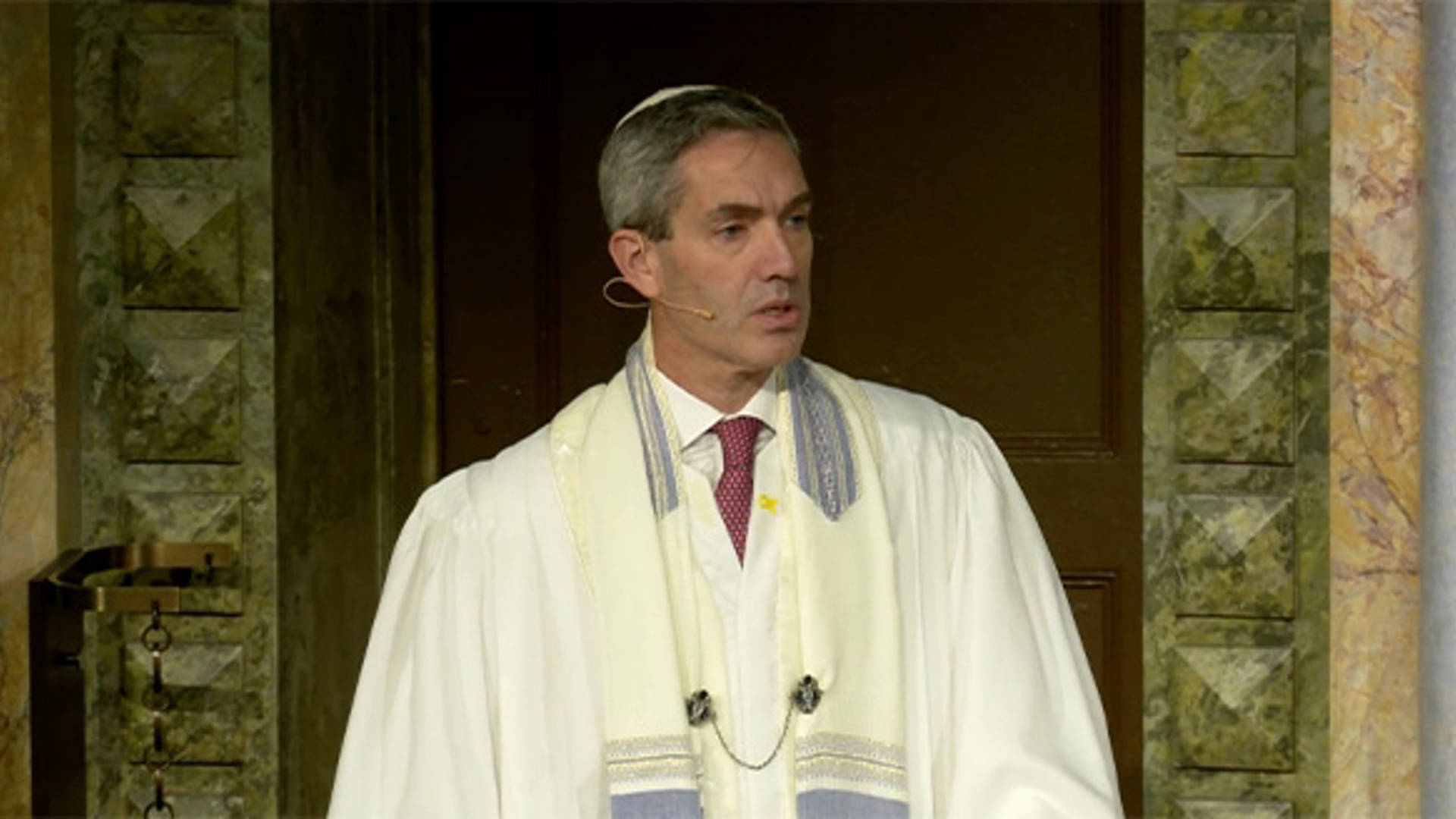

Of all the links and articles and videos and memes that have been sent to me since the October 7 attacks, the one I find myself returning to is a human-interest story shared with me by my dear friend, mentor, and former boss, Rabbi Michael Siegel of Anshe Emet in Chicago.

The incident took place this past summer at the Hecht Museum in Haifa, one of the finest collections of archaeological specimens in the world. The Geller family were having a day at the museum when their four-year-old, Ariel, decided he wanted to look inside a big clay vase sitting on a pedestal. Ariel’s parents took their eyes off him for a split second. Ariel was curious, he pulled ever so slightly on the three-foot jar, reached into it, and yes – you guessed it – caused it to topple and shatter. A rare, fully intact Bronze Age artifact predating the reigns of Kings Solomon and David, now scattered across the museum floor. When I first read about it, I cringed for Ariel’s folks; it is every parent’s nightmare. As I reflected on the incident, my thoughts turned more serious – the broken jar an image that finds ready application for the year gone by. Shattered lives, shattered dreams, and a shattered sense of security. The vessel of the Jewish people, once whole, now in broken shards on the ground.

The metaphor of Israel as a shattered vessel is an ancient one. Long ago, when the prophet Jeremiah preached to the Kingdom of Judah in the years prior to the fall of Jerusalem, our nation stood at the edge of national disaster, caught between competing external forces and spiritual decay from within. Jeremiah’s rhetoric (if you ever wondered where the word “Jeremiad” comes from) drew on the image of a potter and his vessels. “Go down to the potter’s house,” Jeremiah is commanded (18:2). “As one smashes a potter’s vessel . . . so too the people and the city” (19:10–11). A broken vessel is our people’s most ancient and most enduring symbol for the fragility of our nation, for impending disaster, and the irreversibility of God’s judgment upon the people of Israel. It is why we break a glass at every Jewish wedding. An image that has been there all along, it cuts a bit too close to home this year. None of us need look far to see that which is beyond repair, that which is shattered and broken on the ground.

This Yom Kippur, for reasons both obvious and urgent, we carry a collective feeling of brokenness. But in this moment, our Yizkor moment, we make room for our personal sorrows as well. The loved ones we carry in our hearts always, our mothers and fathers, husbands and wives, sons and daughters, brothers and sisters – those friends and family members to whom our thoughts turn during these sacred remembrances of Yizkor. We carry our personal losses even as we bear the sorrows of our people.

And here too, in the personal sphere, the image of a broken vessel finds ready application. In the hands of Jewish mystics, the imagine of a broken vessel is transformed from loss alone to the first step in a process of cosmic healing. In fact, one school of Kabbalah, as taught by the sixteenth-century mystic Isaac Luria, is founded on the very concept of shattered vessels, sh’virat ha-keilim.

I am no mystic, but the basic outline of Lurianic Kabbalah is as follows. When God set out to create the world, God, being God, was everywhere. In order to make space for the world to be created, God had to pull back or contract the divine presence, to do what in Hebrew is called tzimtzum. God contracted, the world was created, and the divine light was channeled into a vessel. A finite vessel, however, cannot contain an infinite God, at least not for very long. Under pressure from the divine light, the vessel broke and shattered, and sparks of divine light spread far and wide throughout the universe. The imagery is poetic and powerful and made a world of sense to Luria’s generation. Remember, this was the sixteenth century, following the expulsion of Jews from Spain. As Jews were dispersed across the globe, the image of scattered sparks was not an abstract one; it spoke directly to the dispersed condition of the Jewish people.

All of this, however, is not the place where Lurianic Kabbalah ends, but where it begins. As Jews we believe that every human being contains a spark of the divine. The sparks that flew forth may be separated from the vessel which initially contained them, but the sparks persist in the universe for eternity. The task of religious living is to find those sparks, to retrieve those sparks, and to restore the divine light – a process known as tikkun, mending. The sparks are scattered, but they are not lost. They are within us; they are us. In fact, the act of retrieving a lost spark, a lost soul, remains, in the eyes of the mystically minded, the holiest mitzvah of all.

The image of divine sparks is, I believe, not just about mysticism but about memory, about this very moment of Yizkor. What is it, exactly, that one does during a Yizkor service? We are all, as the High Holiday prayer book reminds us, finite creations – like a passing shadow, a fading cloud, or a broken shard. There is a reason the call of the shofar is shevarim, from the Hebrew root meaning “broken” – the sound and the language alerting us to the fragile and fleeting nature of the human condition.

The grief we feel in this moment is a sorrow born of the fact that our loved one is no longer. Grief is the price we pay for love. We want nothing more than to have them back – their quiet counsel, their roaring laughter, their gentle touch, their unconditional love. The shards of their mortality, the vessel of their lives, are beyond retrieval. Each of them, and by extension, each of us, is broken.

And yet, and yet, like the mystics of old, in our brokenness, we still yearn for repair, healing, and restoration. The vessel may be no longer, but the neshamah, the soul, the divine spark endures. The memories of our loved ones, our recollections of them and the values they held dear. As the poem goes, “At the rising sun and at its going down; We remember them. / At the blowing of the wind and in the chill of winter; We remember them. / For as long as we live, they too will live, for they are now a part of us. We remember them.”

By such a telling, the Yizkor service itself becomes an act of restoration, each remembrance a reaching out and a retrieval of the spark of our loved ones. Some were granted length of years, some lives cut were short in their prime. Every life, by definition, is bound by the limitations of human mortality; at some point the vessel gives out. But that spark is eternal. - If we reach for it, that spark can be carried from one generation to another. Memories of loved ones can grow faint as an echo; they can also rise like a song at dawn. At Yizkor, the spark, the memory of our loved ones seeks entry into this sanctuary. A light to our darkness, a lamp to lead us forward. Yizkor does not make us whole again, the continued physical absence of our loved ones denies us what once was. Yizkor does, however, offer the promise of tikkun, the knowledge that even as our loved ones are absent from our lives, their presence continues to illuminate our path forward.

Brokenness is our shared condition, but it need not be the end of the story – not for any of us nor, for that matter, for young Ariel Geller with whose story I began. The museum authorities quickly understood that the breakage was not an act of vandalism, just the work of a curious and energetic boy. The museum director reached out to the family, expressing that his concern was not the broken pottery, but the well-being of the boy. They were worried that Ariel would feel ashamed, that neither he nor his family would ever want to walk back into a museum again. Ariel and his family were treated to a special tour – the only noticeable difference in the exhibit a new sign reading “please don’t touch.”

As for the broken vessel, despite expert restoration, the cracks and damage are visible on the jug. A small piece was even purposely left out, so that the restored artifact is noticeably incomplete. “Everything,” explained the museum’s curator: “that happens to an object is part of its story, even the missing part,”

Like a passing shadow, a fading cloud, a broken shard. The lives we live, the lives we remember are fragile and finite. With cracks all around, and some pieces missing forever, we turn our eyes to the heavens, and through the darkness we see the sparks landing ever so gently in our hands and upon our hearts. We reach out for them. We gather them up one by one, the memories of our loved ones, drawing them close and holding them dear, always, and especially at this time of Yizkor.

Kamens, Sylvan and Jack Riemer, “We Remember Them.” In New Prayers for the High Holy Days, ed. Rabbi Jack Riemer (New York: Media Judaica Press, 1970)