“Israel is at war – total war.”

With these words my grandfather began his sermon to his congregation in the days following the outbreak of the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

“Israel is at war – total war. . . . Israel is engaged in a life and death struggle, a struggle for its survival. One hundred million Arabs against three million Israelis. How many of Israel’s young people who mobilized on Yom Kippur, who left from shul, from home, from wherever they happened to be, who went out confidently and courageously, will return wounded and mutilated? How many flowers of our youth will never return? On Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur we prayed for life. . . . Today we are not asking for ourselves – today we are praying for the survival of Israel.”

I never knew my grandfather, the Reverend Dr. I.K. Cosgrove, rabbi of Glasgow Scotland’s Garnethill Synagogue. Aside from a photograph of him holding me and a lifetime of stories about him told to me, my impressions of my grandfather come by way of a handful of his handwritten sermon notes that my father saved following my grandfather’s death. The final sermon of his in my possession is the one from which I just read. He delivered it the first day of Sukkot, October 11, 1973. He died just a few weeks later. That day he implored his community to take action, to make a life-saving transfusion of damim, the Hebrew word that means both “money” and “blood,” to do whatever was needed to save Israeli lives. He spoke of his love for Israel and the importance of Jewish unity. And while he expressed confidence that Israel would prevail, in his cross-outs, in the scribbled palimpsest of his sermon notes, I can sense his anxiety, his uncertainty about the outcome. Israel was attacked on October 6. On October 7, Syria captured the Golan. On October 8, the Egyptians destroyed over fifty Israeli tanks in a thirteen-minute battle. I don’t know what my grandfather knew or didn’t know that day, but I can read his words and I can sense the shake of his hand. “Kol goyim s’vavuni, the nations have surrounded me,” he quoted Psalms. “Who will live and who will die,” he cited from the High Holiday prayer book. It was as dire and dark an hour as the young Jewish state had ever known.

For those who remember 1973, and I imagine many here do, then you probably remember not only where you were that day but how you felt. Arab armies pouring across the Golan Heights and Sinai’s shattered Bar-Lev Line, harrowing reports of battle, a face-off with the Soviets, the oil embargo and the apocalyptic visions triggered by it all. Over these last weeks I have heard many people share recollections of where they were on that Yom Kippur, when Israel’s fate was hanging in the balance. And whatever memories we have here in the diaspora, they pale in comparison to the memories held by Israelis themselves. There were 2,656 soldiers killed in action, over 12,000 wounded, hundreds captured, many of them subjected to torture by the enemy.

We here at Park Avenue Synagogue need look no further than the father of our own Cantor Schwartz, Yehuda Schwartz. Yehuda was a new father to his five-week-old daughter when he was called up to his tank unit that Yom Kippur day. He went up to the northern front, going up the Golan into battle as others fled down in the other direction. When his tank was hit, he survived, thank God, but not without suffering severe burns. I think of Azi’s mother, Yocheved, who left her newborn daughter at home so she could go to Rambam Hospital to see her husband, his burns so severe that she was unable to recognize him until she heard his voice. As Azi’s father would later reflect, there were no heroics that day. Truth be told, there wasn’t even much of a battle. The real battle came after the war: the battle of recovery, the battle of every soldier and every soldier’s wife, daughter, and son, every soldier’s mother and father – many who were themselves Holocaust survivors – to come to terms with the trauma of the war. Shattering as the loss of life and the physical wounds were, the psychic trauma on the soldiers, their families, and the nation was only just beginning.

Israel would never be the same, the shockwaves of the war reverberating through the country into the years to come. The war revealed Israel’s vulnerability. The hubris of the country’s post-1967 complacency, referred to as the conceptzia, was shattered. Some of you may recall the image of Motti Ashkenazi stationed outside Golda Meir’s office in the months after the war holding a placard proclaiming “Grandma, your defense minister is a failure and 3,000 of your children are dead.” You may recall the Agranat commission, the waves of protest over the government’s lack of preparedness and handling of the war. By April 1974, both Prime Minister Meir and Defense Minister Dayan had resigned their posts. By the 1977 elections, Meir’s Labor party had given way to Begin’s Likud.

In retrospect, the trauma of the war gave rise to at least two major movements. Though the ultranationalist Orthodox right-wing settler movement, Gush Emunim, technically began following 1967’s Six-Day War, the Yom Kippur War functioned as its call to action in that it pressed the issue of Israel’s security and territorial integrity. It was a movement for settlement expansion reflecting not only a religious and ideological mission, but also a belief that the territories were vital for Israel’s security. On the other side of the ledger, Israel’s Peace Now movement also began in the aftermath of 1973. The trauma of the war led many Israelis to reevaluate the costs and consequences of a prolonged conflict and thus the emergence of both secular and religious Israelis advocating for a negotiated settlement based on the principle of land for peace – without which the statesmanship of Kissinger, Begin, and Sadat may have come to naught. Two movements born of a single trauma – representing two diametrically opposed visions of Israel’s future – a division that continues to play out to this very day.

It is fifty years later, it is Yom Kippur, and once again Israel is at a tipping point. It is not, thank God, 1973. Israel is strong, no longer David to the Goliath of the Arab world. Not only is the Jewish state fully capable of defending itself, but it has in recent years forged and continues to forge relationships with countries with whom the thought of peace would once have been unthinkable. The threats Israel faces are not what they were in 1973, and we do neither Israel nor ourselves any favors by letting historic anniversaries lead us to hysterics. And yet the challenges Israel faces today are historic, monumental, and existential in their own right. Fifty years later, we gather on Yom Kippur with a new generation’s fears and concerns regarding the security and survival of the Jewish state.

Our year in review is not a pretty one. Last fall’s tight election gave rise to the most hardline ultra-nationalist right-wing government in Israel’s history. A judicial overhaul process has split the country, thirty-eight weeks and counting of pro-democracy protests on Tel Aviv’s Kaplan Street and on streets across the country – protests and counterprotests – seven million Israelis on the streets in the past year, not to mention strikes in multiple sectors of the economy and the refusal of IDF reserve soldiers to serve. We have witnessed the mainstreaming of racism and homophobia by Knesset members, the forwarding of legislation that would compromise Israel’s status as a liberal democracy, and legislation that would provide blanket exemptions from national service for young ultra-Orthodox men. Israelis have suffered again and again and again from the unstemmed violence of Palestinian terrorists. There have been outbreaks of settler terrorist attacks against Palestinians, and there has been an unprecedented eruption of violence within the Israeli-Arab community. We are witnessing a distancing between American Jewry and the Jewish state, between America and Israel, even as I hear, for the first time in my life, some Israelis – Israelis who have made a career of excoriating American Jews for overreach into Israel’s affairs – now pleading for American Jews to say more, do more, and get more involved in Israeli life. What was once treif has become kosher. By any measure, it has been a stunning, consequential, and defining year for Israel. Unlike 1973, the present challenges to Israel’s security are internal, not external, thank God. But make no mistake: In 2023 Israel is at war – total war – with itself.

Beyond the daily news cycle, the particulars of judicial override and the selection of judges, almost everyone agrees that the upheavals of the hour are about more than just checks and balances, an Israeli Marbury v. Madison moment. Some believe the underlying question is whether Israel will choose to be a Jewish or a democratic state – our present tensions reflecting a fundamental divide between a religious and secular vision of Israel – a theocratic state of Jerusalem or a liberal state of Tel Aviv. Others believe this moment to really be about the settlements, a come-to-Moses moment, if you will, on the two-state solution. Still others see the eruptions of the past year as reflections of grievances long held in Israel’s Sephardic community: It is time, once and for all, to break the Ashkenazi elite’s hold on Israel’s political, economic, and judicial life. Many have noted the similarity of the timelines between Israel’s founding and its present crises and between the founding of our country and the outbreak of civil war – some sort of gestational period whereby issues left unresolved by a country’s founders eventually burst forth. There are those who believe that the root cause of Israel’s troubles lies in the Prime Minister’s desire to retain power and thus avoid criminal prosecution, while others believe Israel’s slide into an illiberal democracy is just a sign of the times, no different than Poland or Hungary or, for that matter, the bare-knuckle reality of minoritarian politics, be it in the Knesset or the US House of Representatives. As far as Israel’s increasingly distanced relationship with diaspora Jewry, many view this year as the year American Jews decided to no longer let their silence serve as a complicit enabler for an Israeli government that does not recognize the Judaism of its diaspora and a diaspora that no longer sees a home for its Judaism in the Jewish state.

And while all, some, or none of these tensions may be operating at the substratum of Israel’s present woes, in my mind the fault line runs deeper, through the Yom Kippur War, but much deeper than that, to the innermost reaches of the Jewish condition, to before the State was established – as deep and far back as the very beginnings of our people.

Let me explain.

Loss, hurt, trauma, and missing pieces, as I explained on Rosh Hashanah, are part and parcel of the human condition. Having narrowly escaped the Damoclean sword, victims of trauma, be it a person or a people, will choose to respond in a multitude of ways, the two most common being anger and empathy. “I have been hurt,” says the former, “and I will never allow myself to be hurt again. My hatred of my enemy and my hypervigilance against my potential enemy is my response to my victimhood.” To paraphrase the political scientist Jennifer Mitzen, to the physically insecure there is ontological security in knowing who one’s enemies are. Another response to trauma involves a posture of empathy and the dogged pursuit of peace. “I have been hurt,” says this victim, “and it is a condition that neither I nor anyone should ever experience. Having survived, having been given a new lease on life, I will leverage every fiber of my being towards ensuring that no human being should ever endure victimhood as I did. I will work to bring peace in this world with the aim that the divine spark in every person is affirmed. Anger and empathy – both well documented responses to trauma, existing within us all.

As Jews, both responses are coded into the DNA of our people. We have had more than our fair share of trauma. Milton Berle was more right than he knew when he quipped that when a person converts to Judaism, they are granted five thousand years of retroactive persecution. But how we respond to that trauma – that has always been the choice that has defined us. Is the take-home of the Purim story Esther’s courage and heroism – a message of light, joy, gladness, gift giving, and tzedakah to the poor – or is it a tale about the wickedness of Haman, the perennial threat of antisemitism, the obligation to defend ourselves and take vengeance upon our adversaries? Both are there; what we focus on is a choice we make. Is the take-home message of the Passover seder one of radical empathy, a reminder that we must know the heart of the stranger for we were once strangers in a strange land? Or is the message that in every generation a new Pharaoh arises to destroy us against whom we must stand vigilant? Both are there; what we focus on – a choice we make. Many of us can probably think of a survivor of the Shoah whose trauma resulted in a lifetime of embittered victimhood; many of us can think of a survivor who responded to their trauma with kindness, liberal values, and overflowing love of humanity. Neither response, in and of itself, is right or wrong. Why one response and not the other? It is not for anyone but that person to know, but it is a difference that makes all the difference in the world.

The Yom Kippur War is illustrative in that two identifiable movements – Gush Emunim and Peace Now – emerged from the war, each reflecting a response to a single trauma. But the Yom Kippur War is just one date and data point in a much bigger story. This year also marks 120 years since the Kishinev pogroms, a series of anti-Jewish riots that prompted many early Zionists, most famously Vladimir Jabotinksy, to turn away from Ahad Ha’am’s “light unto the nations” cultural Zionism towards a Revisionist Zionism of assertive Jewish self-defense. In fact, this year marks exactly one hundred years since the publication of Jabotinksy’s iconic “Iron Wall” essay, in which he urged, in the wake of the Tel Hai massacre, an uncompromising militance in the face of Arab opposition to the nascent Jewish state. That same year, 1923, Jabotinsky resigned from Weizmann’s moderate Zionist movement to found Betar, a program aimed at educating youth in a militant national spirit.

The late Israeli poet Haim Gouri, in the wake of the Eichmann trial, described the soul of Israel by likening it to our patriarch Isaac who narrowly escaped his near sacrifice on Mount Moriah. “Isaac,” Gouri wrote, “was not sacrificed. . . . But he bequeathed that hour to his offspring. They are born with a knife in their hearts.” I think of that knife in the hearts of Israelis in the poetry of Uri Zvi Greenberg, the poet of Israel’s national right who, in the wake of the Shoah, urged Jews to never, not even when the Messiah comes, turn their swords into plowshares for fear of becoming victims once again. I think of that knife in Moshe Dayan’s 1956 Gettysburg-esque funeral oration for the slain kibbutznik Roi Rotberg, in which he spoke of “the young Roi . . . whose yearning for peace deafened his ears and he did not hear the voice of murder waiting in ambush.” Swords or plowshares, defending Jewish blood or pursuing universal values: two visions of Zionism – one on guard from impending catastrophe, one seeking to be a light unto the nations – both born of trauma.

This is the fault line that runs through the history of our people since our founding. This is the tension that has defined, presently defines, and will continue to define Israel. Aside from the rather significant fact that the Israeli far right now wield power and are thus left unchecked in their messianic extremism, the ideology they espouse is not new. Israel’s ultra-nationalist government is merely the latest instantiation of an ideological line that has always coursed through the veins of our people. As for those protesting on the streets of Tel Aviv and, for that matter, liberal American Jews alienated by an illiberal Israeli government – they have every right to be shocked; but they should not be surprised. Indeed, if there is a silver lining to come of all this, it might just be that Jews in Israel and America will be more engaged and active in the short-, medium-, and long-term tactics necessary to create an Israel that reflects their lived values and, I would add, the founding documents of the State of Israel itself.

All of which brings me back to where I began. It is Yom Kippur fifty years later and Israel’s fate yet again hangs in the balance, and, like my grandfather before me, I wonder what is the message that my community needs to hear. My writing instrument may be a bit more sophisticated, but my thoughts are just as fumbling. My hand too trembles. I know my opening line. It echoes that of my grandfather: “Israel is at war – total war – with itself.” It is where I go from there that my struggle begins.

Israel is not, in my opinion, in a competing truths moment – what the rabbis called an eilu v’eilu debate – the views of both sides equally reflecting the will of a living God. I have no great reveal for you today. You know what I believe in; I have been saying it for the last sixteen years. Women’s rights, gender equality, minority rights, separation of state and religion, a two-state solution, religious pluralism, liberal democracy and yes, as stated in Israel’s Declaration of Independence, an Israel “based on freedom, justice, and peace as envisaged by the prophets of Israel.” I may live at the edge of the west, but libi b’Kaplan, my heart is on Kaplan Street. Because when you tune out all the noise, it boils down to whether Israel can and will remain both a Jewish and a democratic state, and I know which side I am on.

I hold no expectation that everyone agrees with each other, with me or for that matter, your fellow congregant. We are a big tent. Indeed, if Park Avenue Synagogue has a differentiated place in the landscape of New York and national Jewish life, it is to model a single community capable of housing a plurality of views as to what is and isn’t in the best interest of Israel, a secure, Jewish and democratic Israel.

Which brings me to my second point. Convinced as I am of the rectitude of my views, I also believe it to be a misrepresentation of both the Jewish soul and the harsh realities of our world to aspire towards some sort of unidimensional liberal Zionism. Our world has not been kind to the Jews. One does not need antisemitism to make a case statement for a Jewish state, but unfortunately, in every generation, our enemies provide us with one. Israel and the Jewish people have real enemies; our trauma is not imagined. Lovely as it may be to imagine Israel as a light unto the nations, land of hope and dreams for liberal values, we must never forget that Israel was neither handed to us on a silver platter, nor will it be sustained by the kindness of strangers. There is still Iran, there is still Jenin, there is still anti-Zionism and antisemitism on college campuses and across the globe. The threats to Israel are not going away anytime soon. We need to be vigilant and, as the prayer book teaches, we need strength if we are to achieve peace.

In other words, what we need is a Zionism that stands in defense of the Jewish lives, and a Zionism that stands in defense of liberal values. We need both because if we have only the latter then we will have a defenseless state, and if we have only the former, we will not have a state worth defending. We need both because the two strands of Zionism mitigate the excesses of each other. We need both because both are authentic expressions of the Jewish soul. Most of all, we need both because it is in those moments when Israel is able to demonstrate the presence of both, that Israel is at its best. When the same Prime Minister Menachem Begin who bombed Iraq’s Osirak nuclear power plant picked up sixty-six Vietnamese refugees that no other country would take in – that is Israel is at its best. When thirty years ago this fall, Prime Minister Rabin, after a lifetime of service in defense of Israel, signed the Oslo accords explaining, “We must fight terrorism as if there is no peace process and work to achieve peace as if there is no terror” – that is Israel is at its best. Or just this past month, when a terrible earthquake hit Morocco and Israel offered its rescue teams regardless of the history between the two countries – that is Israel is at its best. The irony of the present moment is that what is dividing Israel right now could also be its greatest strength if only the two sides could find a way to let their competing impulses exist within a single body politic. Lest we forget, the tragedy of the binding of Isaac wasn’t just the trauma at the top of the mountain. The tragedy was that the two who walked up the mountain together – va-yeil’khu shneihem yahdav – walked down each alone. We need to learn to walk and talk and live together.

The last major battle of the Yom Kippur War occurred on October 24 and 25 in Suez City. A cease-fire had been declared, but in what in hindsight was a disastrous decision, before the arrival of UN observers, Israel made a final push to occupy Suez City, a logistical base for Egypt’s then-surrounded Third Army. Israel’s 66th Battalion, the paratroopers who had famously captured Ammunition Hill in the Six-Day War, were sent in for the mop-up mission. They had no advance intelligence and no battle plan. They entered along the main artery of Suez City, which by that time was mostly deserted. Upon reaching the second intersection, the battalion was caught totally off-guard when grenades, gunfire and RPGs rained down on the ambushed soldiers.

Upon regaining consciousness, one soldier, Micha Eshet, opened his eyes to see that many of his fellow soldiers were, like him, wounded, and many others were dead. Micha’s legs felt like they were on fire, and he couldn’t hear a thing. Together with the other wounded, he crawled out of his vehicle on his hands to take shelter in an adjacent building. Two miles deep into the city, no rescue mission was on its way, and the surrounding Egyptians continued to fire on the huddled soldiers. It would be just a matter of time before they penetrated the building. Micha recalls being given a gun with a single bullet in the chamber and the order to burn all the documents he had on his person, which he did, save a drawing that his five-year-old daughter Sharon had given him. As nightfall arrived, some soldiers in the unit thought it better to stay and wait for help while others argued that it was time to make a run for it. At 2:30 in the morning, the surviving soldiers decided it was now or never. In the dark of night, for two hours –those wounded dragging their legs and the few healthy ones bearing others on stretchers wound their way through the streets of Suez City toward the spotlight that indicated the Israeli position. As Micha and his fellow soldiers reached safety, the sun began to break through the clouds and morning mist. Exhausted and out of breath, Micha collapsed on the ground looking at the most beautiful sunrise of his life.

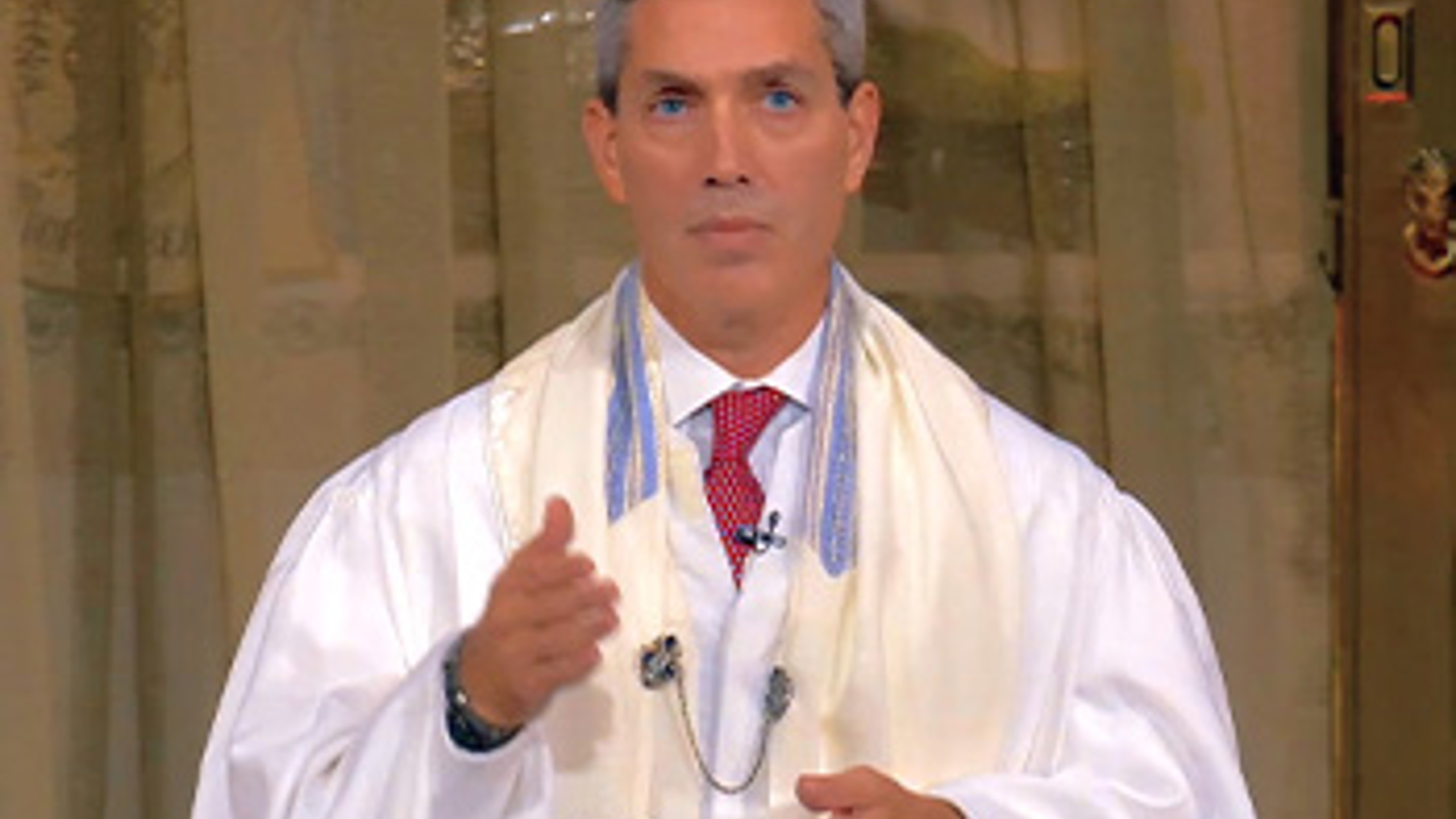

Over 80 dead and 120 wounded. The Yom Kippur War ending as ignominiously and traumatically as it began. Micha, I am glad you are here with us today. I am glad you and Shari are here. I am forever grateful that you took me in as your adopted son when I lived in Israel after college. You instilled in me a love for Israel that has never wavered. That cute brunette I met in Israel – you’ll never believe – she became the rebbetzin of Park Avenue Synagogue. Micha, I am proud of your leadership in Brothers and Sisters in Arms – IDF combat veterans for a Jewish and democratic Israel – out in force at Friday’s pro-democracy rally. Their presence reminded us all what it is that Israel has fought for, fights for today, and will continue to fight for. I hope my speech at the rally made you proud. Your presence here this Yom Kippur makes us all proud.

Most of all, Micha, I am excited for the party being planned for October 25 for the members of your battalion who fought fifty years ago. A day, you told me, reserved for smiles and laughter. You are even calling it a birthday party. Why a birthday party? Because on that day, you and your friends were given life. Having survived the trauma of the darkest of nights, you emerged understanding that the miracle of life, the miracle of the State of Israel was something not just to be defended, but nurtured and treasured. Micha, when you return to Israel, let them know that we here in America, we here at Park Avenue Synagogue, feel the same way. We stand with you, with all of Israel, as we always have, and so we always will.

Penslar, Derek. Zionism: An Emotional State. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2023.