Sadie Goldstein had just moved into her big, new apartment. She wanted the world to know, and the first person she called to visit was her old friend Esther.

“Mazel tov!” said Esther, “I would love to come for tea. Where do you live?”

“I live,” Sadie said, “in a beauty of a building, 993 Park Avenue. It has a gorgeous front door, so when you arrive, give it a good push with your right elbow, and as you walk in, use your left elbow to close the door behind you. Once you are inside, you will see the list of names with the buzzers; take your left elbow and ring my apartment so I can buzz you in, and then use your right elbow to press down on the handle to get into the lobby. Walk to the elevator and use your right elbow to press the ‘up’ arrow. Once you are in the elevator, use your left elbow to press the button for the top floor. Walk down the hallway to my apartment and ring the doorbell with your right elbow, but feel free to just push the door open with your left elbow. You’ll come in, I’ll show you around, and we’ll have tea – I can’t wait!”

“Sadie, I can’t wait either,” Esther replied, “but if you don’t mind me asking: What kind of directions are these – all this business with the right elbow and left elbow? What’s with all the elbows?”

“Well,” said Sadie, “you’re not thinking of coming empty-handed, are you?”

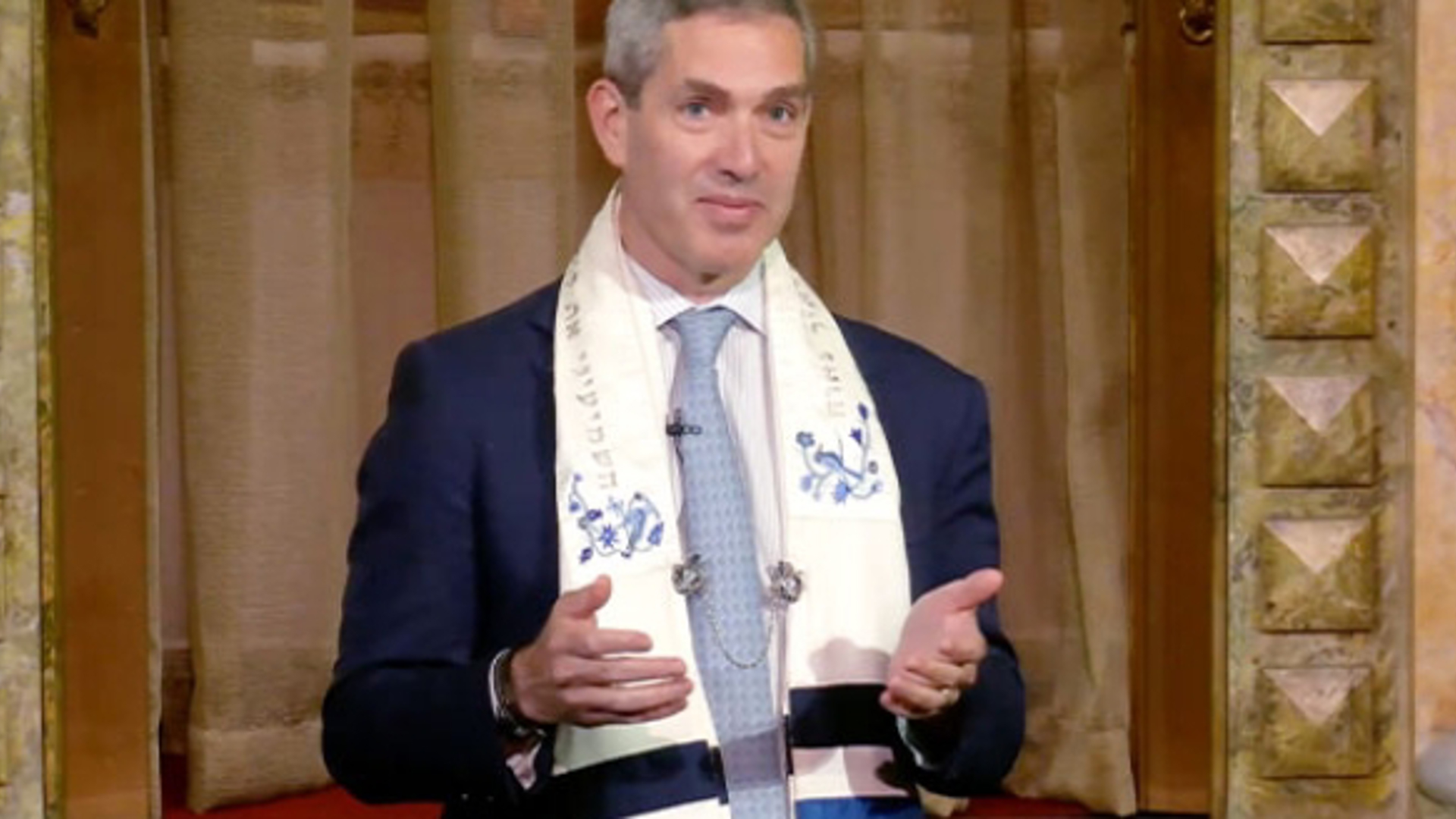

This morning I want to speak to you about being a guest.

We Jews have no shortage of sources and stories about the importance of hakhnasat orhim, the mitzvah – the commandment – of welcoming guests. From the very beginnings of our people, when Abraham and Sarah sat at the opening of their tent to welcome every passerby, hospitality ranks high in the pantheon of Jewish values. Literally, we should always be prepared to set a place for a person. But hospitality is a spiritual calling as well. “You shall know the heart of the stranger, for you were once a stranger in a strange land,” teaches Exodus. For Jews, to be hospitable is a religious posture to which we aspire, be it toward refugees at our borders or in the way we relate to anyone seeking entry. To be inclusive, to have empathy, to always make room for the humanity of another person.

But that is not the hospitality I want to discuss today. Today I want to talk about what it means to be a guest. As Emily Post, my mother, and Sadie Goldstein know, to be a guest involves following certain rules – a role that calls on us to act in certain ways. When you arrive or before you arrive, you don’t come empty-handed. You bring a gift, a treat – a bottle of wine or flowers – for your host. And then, of course, after you leave, you send a thank you note, ideally handwritten but at least an email expressing gratitude for your host’s hospitality. When you are a guest, you offer to pitch in and clear the dishes. If you are there for a while – more than a day or two – you offer to help pay for the groceries. When you are a guest, you make sure to clean up after yourself, leaving things in as good – if not better – shape than you found them. A good guest doesn’t overstay their welcome, as Benjamin Franklin wrote: “Guests, like fish, begin to smell after three days.”

There are all sorts of rules that go with being a good guest. The list is an evolving one, but at its core – the thread that ties all the rules together – is to always remember that you are a guest. You are the visitor; you are only there for a short while, present on account of someone else’s good graces. Soon enough you will be gone, but your host will still be there, and so you act with great care and respect for your surroundings. To be a guest means to comport oneself with an attitude of gratitude and humility. Most of all, when you are a guest, you are deferential to the customs and behaviors of your host. You might act a certain way in your own home – put your feet up on the table, leave the dishes in the sink, or dance around the kitchen in the refrigerator light – but when you are guest you act according to the custom of your hosts. Why? Because it’s their place, not yours. You, my friend, are the guest.

In Hebrew, the mitzvah of hosting is hakhnasat orhim, roughly translated “welcoming guests.” Best I can tell, there is no equivalent term for the mitzvah of being a guest. The closest we have is the rabbinic principle called minhag hamakom – minhag meaning “custom” and makom meaning “place.” The gist being that when one visits a place with customs – minhagim – different than one’s own, one follows the minhag hamakom, the custom of the place, not one’s own. For instance, in the Cosgrove home the minhag is to say kiddush, the blessing over the wine, standing up; but when I am in someone else’s home where they sit, I sit – happily so. My personal practice is to pray according to the Ashkenazi tradition; when I visit a Sephardic synagogue, I pray according to their tradition. There are a million examples: how one prays, how one observes ritual, even how one dresses. Some customs are more stringent, some more lenient, but the principle is one and the same: A visitor does not deviate from local custom. Our Torah reading makes reference to the idea in connection with the Passover ritual: “When a stranger resides with you . . . there shall be one law for you – stranger and citizen alike.” (Numbers 9:14-15) Why? The tradition offers a few reasons: Because to do otherwise could split a community; because to do otherwise, to presume that that community I am visiting should follow my custom is to commit the sin of yuhara, spiritual arrogance. The primary reason is the most the obvious one: You are a guest, so act like one.

It never occurred to me that minhag hamakom – the ethics, if you will, of guest-hood – was a topic worthy of a sermon, a subject in need of defense. I figured everyone just sort of got it. But then a few weeks ago, there was a guest here in the synagogue, whose name I do not know, who was visiting from out-of-town. As many people who are here for the first time do, he took out his cell phone and started filming something. A synagogue regular politely tapped him on his shoulder and explained that the minhag, the custom here is that we keep cell phones off and out of sight during the service. My kids were in town that weekend, and unbeknownst to the guest, I was sitting in the pews with my kids a few seats over. The visitor refused, pointing to the screens, the cameras, and the lights, and saying how ironic it was that they were in use, but he shouldn’t use his phone. The regular responded politely, kindly, much more kindly that I might have, that ironic or not, it was a matter of decorum in our house of prayer. Thankfully, the visitor eventually put his phone away, but only after he got in a final dig as to how hypocritical he found our policy.

It was a fascinating exchange to overhear, not so much for the merits of the discussion – about which reasonable people might disagree. What made it fascinating, and troubling, was what the exchange revealed about that visitor. He would be here for just two hours, passing through by his own choice; nobody was forcing him to be here. Idiosyncratic as they may be, we do have customs here at Park Avenue Synagogue, such as not using cell phones and expectations regarding whether people wear head coverings and prayer shawls as they enter the sanctuary, sit on the bimah, or take an honor at the Torah. There are principles for which we stand as a community, principles that reflect our egalitarian spirit, that define us as this community and not a different one. We may need to do a better job of communicating our customs, but that person that day, he acted with yuhara, like he owned the place; he had forgotten what it means to be a guest.

I fear that the behavior that person displayed that day is not unique to him. And my concern is not just this sanctuary. My fear, in a sentence, is that far too often, far too many people in our world have forgotten what it means to be a guest – that people go about living their lives thinking that wherever they are, they own the place. The story is told about an American tourist who travelled a great distance and at great expense to pay a visit to the greatest rabbi of the nineteenth century – the Hofetz Hayim. The man finally arrived, reached the rabbi’s home, knocked on the door, and was astonished to discover that the famous rabbi’s home was a simple room filled with just books, a table, and a bench.

“Rabbi, where is your furniture?” The tourist asked.

“Where is yours?” replied the rabbi.

“Mine?” asked the puzzled American. “But I’m a visitor here. I’m only passing through.”

“So am I,” said the Hofetz Hayim.

We are all – each one of us and all of us together – just passing through, guests in this world. We know this to be the case, but we sure don’t act like it. Not that we needed it, but as we all put on our N-95 masks again this past week, our city received a very pointed reminder of the ecological precipice we are standing on – if not falling off. A world where warring countries blow up dams, perpetrating unspeakable ecological damage for military gain. The rabbis of the Midrash teach that when God created the first man, God took him and showed him all the trees in the Garden of Eden, and said to him: “See My creations, how beautiful and exemplary they are. Everything I created, I created for you. Make certain that you do not ruin and destroy My world, for if you destroy it, there will be no one to mend it after you.” (Kohelet Rabbah 7:13). This world of ours, it is neither ours nor is it replaceable. We are but stewards, guests passing through who hopefully will live by habits that will make this world habitable by our children and grandchildren.

The school year is coming to end; summer is in the air. Tonight, I will be getting on a plane to lead the synagogue’s Young Family trip to Israel. I can feel the year winding down. By so many measures – as a community, personally – it has been a fabulous year. There is much for which I am thankful, so many reasons I am filled with gratitude and hope. But I do look out at this fractured world in which we live, its ecological crises, its military conflicts, its toxic and polarizing vitriol, and I do wonder. I wonder what it is that our world needs now, what is that one ingredient which, if we were all to have it, the world’s problems might not be solved, but the people of the world – at the very least – might be resolved to work together to address them? Maybe, just maybe, the missing ingredient is the daily if not hourly reminder that we are all just guests in this world. How much kinder, more deferential, humble, patient, and spiritually curious would we all be? How, were we all to think of ourselves as guests, would we pick up after ourselves, inquire into the condition of others, fill our days with “excuse mes” “pleases” and “thank yous,” and respect that while we personally may do things a certain way, we hold no expectation that others do so, and so we embrace the diversity of our world. In our conversations, in our places of work, with friend and stranger alike how might we act like guests? We may not change the world, but we can be the change we seek in this world – a goal that I would like to believe is worthy unto itself.

A final thought, and not an easy one. Yesterday, as many of you know, I stood with a synagogue family as a mother and father buried their nine-year old son – a beautiful child whose light shined brightly and all too briefly – taken from this world by the ravages of cancer. As the parents took their leave of the gravesite, after doing the unimaginable act of burying their child, the community present recited the traditional phrase, Hamakom y’nahem et’khem, may God comfort you. In that moment, I remembered that another name for God is makom, the same word as in minhag hamakom. Meaning that another way to understand the commandment to follow the “custom of the place,” is to follow “the custom of God.” And in that moment, I thought to myself that some people live in this world to ninety and others only to nine – but all of us are just guests passing through this world. Shouldn’t we all aspire to follow minhag hamakom, the custom of God? That in our fleeting lives of indefinite length, we should aspire to follow the attributes of God, filling each day with love, forgiveness, beauty, joy, generosity, purpose, and holiness. Friends, we are guests, here for but a hot flash. Let’s act as such and live in this place and leave this place in better shape than we found it.