This year marks the one hundredth anniversary of the publication of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s short story, “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.” The story is brief enough, but if you want to do it on the cheap and enjoy the added bonus of two hours alone with Brad Pitt, you can watch the 2008 film adaptation. Born in antebellum Baltimore, Benjamin arrives in the world as a man somewhere in his seventies – fully formed, speaking, and grey-bearded. At five, he is sent to kindergarten, but being an older man, keeps falling asleep in school. At eighteen, he tries to enroll in college at Yale but is rejected by the admissions officers who believe the middle-aged man is mocking them. Benjamin reaches his prime in his twenties, takes over his father’s business and doubles it in size, gets married, fathers a son, and, and at the height of his powers, enlists in the Spanish-American war to emerge as a decorated war hero. Hitting fifty, Benjamin, now presenting as a man in his twenties, finally goes to college, enrolling at Harvard to play football if for no other reason than to exact his revenge on Yale’s football team for having rejected him decades earlier. As Benjamin enters his teens, he realizes that he can no longer compete with the men of college football nor, for that matter, understand the content of his classes. Benjamin returns home to his son, who is now older than his father and embarrassed by him. Younger and younger Benjamin grows, the clock running backwards, into adolescence, into childhood, into infancy, and then, as the story closes, into a dark nothingness.

Aside from its compact elegance, the appeal of Fitzgerald’s story is that it serves as a meditation on the universally shared but often uncomfortable subject of aging. Fitzgerald credits the idea of the book to Mark Twain’s comment that it is a pity that the best part of life comes at the beginning and the worst part at the end. His book is a journey through an imagined alternative – were we to start old and grow young – an option that Fitzgerald entertains, but ultimately seems to reject. In other words, while we can all opine as to whether youth is wasted on the young, the direction of life is what it is, and the alternatives, fictional included, are not much better. To live forever would deprive life of its meaning. As Chaim Potok wrote in My Name is Asher Lev: “Something that is yours forever is never precious.” Nor for that matter, is it an option to stop time. In the words of Golda Meir: “Old age is like a plane flying in a storm. Once you’re in it, there’s nothing you can do.” Imperfect as it is, we are left with the option we have: We age, a state of being that comes with a built-in paradox. On the one hand, growing old is the thing we desire most, far better than the alternative. And yet, it is the frailties that come with aging that are the very things we fear most in life.

Ever since the Garden of Eden, when the first couple ate from the Tree of Knowledge but not from the Tree of Life, this paradox has been baked into the human condition – a condition for which we have developed an abundance of coping tools. The most common path, reinforced by the way secular culture valorizes youth, strength, and beauty, is to cover up the signs of aging as they appear on our faces, in our hair, and on our bodies – a form of denial as understandable as it is odd, given the fact that aging is the one thing we can all count on. Last year, the industry of anti-aging products in our country was estimated to be sixty billion dollars and growing at five percent each year. Other people, the “don’t ever grow up” people, dig in their heels at the sight of gray hair, believing that the effects of aging can somehow be halted by way of desperate assertions of adolescence – a Harley Davidson, a sports car, or . . . an earring – in my mind the cheapest and safest of all the options. The most common coping mechanism, no doubt, is humor. Growing old is the backbone of more jokes than can be counted. We know the story of Sadie and Abe, who are visited on their sixtieth birthdays by a fairy godmother who grants them one wish each. Sadie asks that her lifetime dream be fulfilled to travel the world, and with a wave of the wand – poof! – Sadie is holding cruise tickets in her hand. The fairy godmother turns to Abe, who pauses, and in a moment of daring says: “I’d like to be married to a woman thirty years younger than me.” The fairy godmother waves her wand – poof! – and Abe is now ninety. Humor is our response to that which is both painful and unavoidable. When the famed novelist Agatha Christie was asked what it was like to be married to a prominent archeologist, she responded, “Oh, it’s wonderful. The older I get, the more interested he is in me.” The jokes may be Jewish or not, the jokes may be gender-sensitive or not, but the jokes, like all humor, are coping mechanisms to address the fact and the fear and the blessing of growing old.

Because while many people, hopefully, look to each chapter of life as an opportunity for new mission and meaning, what Arthur Brooks calls finding our “second curve,” longevity necessarily brings with it a cascade of losses. Most obviously there are limitations on one’s physical capacities – the frustrating realization that one simply cannot do what one once could. There are the limitations on one’s cognitive capacities, a series of reversions – in energy, attention and memory. COVID has done no favors to the elderly. First, foremost, and tragically, the loss of life. But COVID has also taken the kishkas out of the living – of all ages, but especially the aged. Over these past years as the world has been turned upside down, millions of seniors have been deprived of the hard-earned and long-anticipated victory lap that was their due – travel, time with grandchildren, time with siblings, and otherwise. It is not just that the physical movement of seniors was circumscribed, but their social circles as well. With every passing year, an awareness that their journey is shared by fewer and fewer. Ask any person between 75 and 105, each one carries a list of friends – Gloria, Suzie, Ruby, Deedee, Roen – no longer of this world. The death of a confidant, the death of a part of one’s very being.

I have always been struck by the scene towards the end of the book of Genesis when the patriarch Jacob, finally reunited with his son Joseph, is brought by Joseph to meet Pharaoh. The two patriarchs, Egyptian and Israelite, greet each other and Pharaoh inquires of Jacob: “How many are the years of your life?” Jacob responds, “The years of my sojourn are 130. Few and hard have been the years of my life, and nor do they come up to the life spans of my fathers.” (Genesis 47:7-9) Jacob has fathered a nation, been reunited with his son, achieved a length of years that is, well, biblical in proportion. And yet, when asked, his years are poor in quantity, in quality, in absolute terms, and certainly relative to his forefathers. Whatever the facts of Jacob’s life, he suffers from a form of depression – an inability to see the good, perseverating on the bad. Acutely aware of his impending mortality; he sees only the diminished road ahead, not the extraordinary road traveled. Jacob’s mindset is a window into the challenges of what it is to grow old.

But the greatest price that comes with the privilege of longevity, is not, I believe, a loss that can be explained by way of biology or physiology. We may not be happy about it, but intellectually we know that nobody – not even Moses, who died at 120 with eyes undimmed – ever reaches the Promised Land. Difficult as the fact of diminished physical and cognitive capacity may be, the real difficulty is the diminished role the elderly perceive themselves to have in this world – the emptiness felt by those who were once at the center of it all, at work, at home, and in the community. The people around whom the universe once revolved and relied, whose every minute counted, now see themselves as diminished in significance, in consequence, and in worth. Beyond a loss of independence, they fear that with senescence comes obsolescence, that everybody has moved on and left them behind. Men and women who built families, businesses, and entire universes, who nurtured, counseled, and guided so many for so long are now, in their twilight years, shunted aside.

And it is this fear, this fear of being cast aside as one ages, that takes center stage on Yom Kippur. In every service of Yom Kippur, we name the fear before God:

Sh’ma koleinu, hear our voice.

Al tashliheinu l’et ziknah, do not cast us off in old age.

Kikhlot koheinu al ta·azveinu, when our strength fails, do not forsake us.

It is, I believe, one of the most searing confessions of this sacred day. We miss the point if we believe that Yom Kippur is a day merely to confront the fact of mortality – who will live and who will die. Yom Kippur is the day we give heed to the voice, the tortured cry, the tears, and the fears of those who stand before the dying of the light. It is a feeling perhaps best explained by the late children’s poet Shel Silverstein, who commented on Sh’ma koleinu by way of a dialogue between a young boy and an old man:

Said the little boy, “sometimes I drop my spoon.”

Said the old man, “I do that too.”

The little boy whispered, “I wet my pants.”

“I do that too,” laughed the little old man.

Said the little boy, “I often cry.”

The old man nodded, “So do I.”

“But worst of all,” said the boy, “it seems

Grown-ups don’t pay attention to me.”

And he felt the warmth of a wrinkled old hand.

“I know what you mean,” said the little old man.

Al tashliheinu l’et ziknah, do not cast us off in old age. Not the fear of death, not the fear of growing old, but the fear that in our old age, we are ignored, abandoned, and pronounced obsolete.

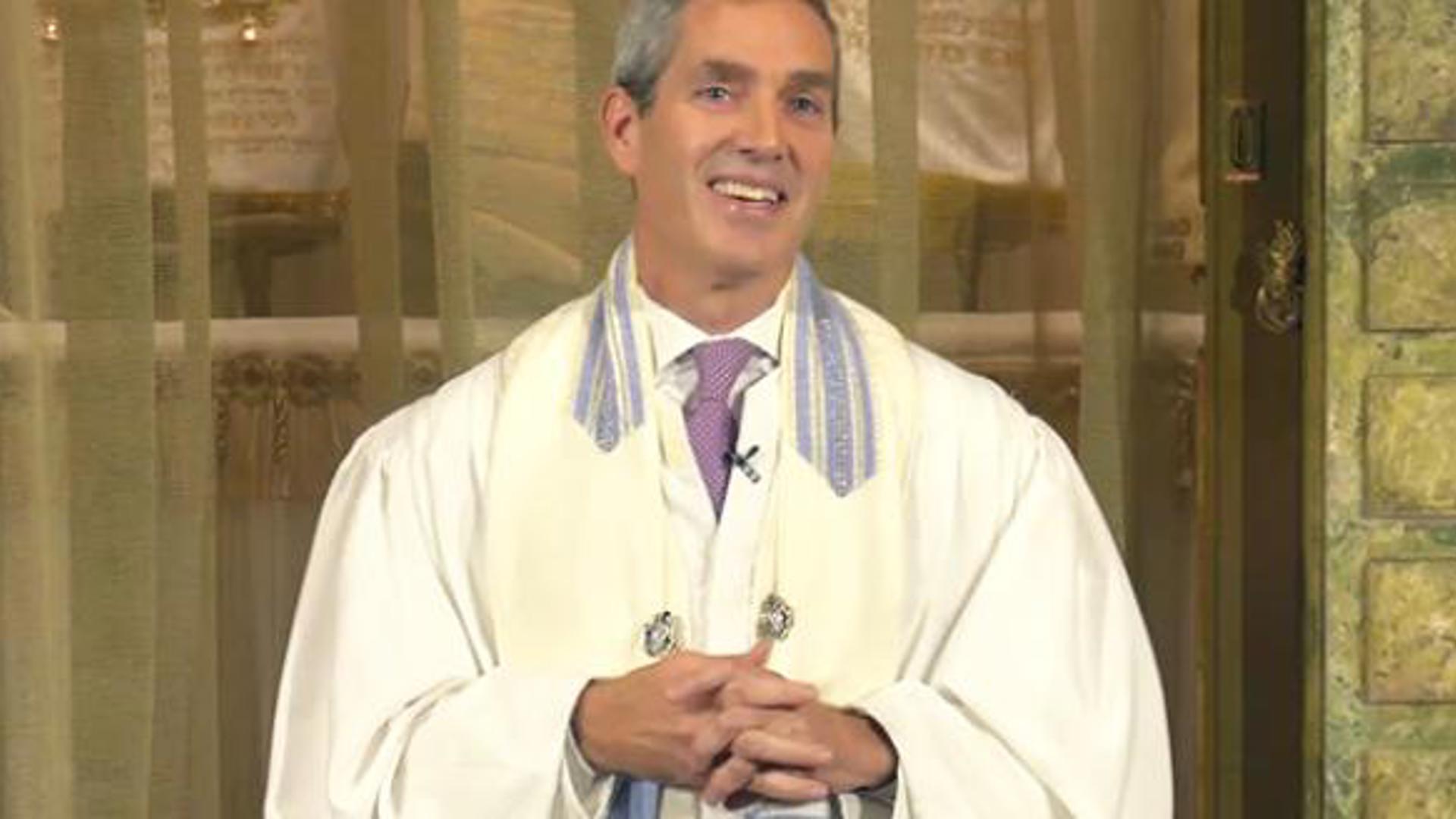

And it is here, at this point in the sermon, that I need to pause. Pause to name something aloud that many in this room are no doubt thinking. I am well aware that many, perhaps half, of the people here are older than I am. People who might be thinking, “Elliot, it is nice that you are acknowledging us. Thank you. And your grey hair, Elliot, tatala, it is sweet. But what do you know, really know, of growing old? Elliot, you have the gift of living parents, may they live to 120, but I have cared for, buried, and mourned mine. What business do you have speaking to your elders about the fear of aging, of being cast off, about the price that comes with the privilege of longevity?”

They are the right questions, questions that are not only fair, but – and stay with me –precisely the point. Because trained though I am as a pastor, I am keenly aware of the limitations of my life experience. Attuned as I may be to the fragile nature of the human condition, neither I, nor anyone for that matter, can fully address the biological or theological questions surrounding human mortality. Which is why I need to clarify. Why I need to specify that while I might be speaking about my parents’ generation, my intended listeners are my generation and the next generation. Because if the diagnosis of the day involves naming the existential loneliness that accompanies growing old, of the adverse consequences of societal attitudes to the elderly, then the members of my generation must hear that it is they – that it is we – who hold the corrective, the antidote if you will, to that very state of affairs.

Let me explain.

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, in a 1961 address at a White House Conference on Aging, gave voice to the existential fear of being found useless and rejected by family and society. “The test of a people,” he taught, “is how it behaves towards the old.” As a Jewish people, the obligation that one generation has to the prior generation, of filial piety, sits front and center. You don’t need to look very far: it is the fifth of the Ten Commandments. Kaved et avikha v’et imekha, honor your father and mother. A commandment whose very placement is significant in that it is grouped with the first four, the “God-centered” commandments, as if to say that honoring a parent is equivalent to honoring God. What does it mean to honor one’s parents? For starters, it involves not sitting in their place, not contradicting them in public, providing them with food and drink, with shelter and medical care. Some of the most colorful stories of rabbinic literature describe the heroic lengths taken by Talmudic personalities in order to honor their parents. The sacrifices in time, finance, and ego make a compendium of filial one-upmanship that every Jewish mother would enjoy. In truth, we should all read the literature because it includes textured discussions about matters ranging from who pays for elder care, how to care for parents with dementia, at what point one can move a parent into group living, what to do if there are conflicts between siblings or spouses regarding care for parents and in-laws, and even the degree to which one should, or should not, honor an abusive parent. To honor one’s parents, incidentally, is a commandment, like tzedakah, that has nothing to do with whether you want to do it or not. We are not told to love our parents like we are told to love our neighbor. The command kaved, meaning honor, is from the root meaning weighty or hard – according to the rabbis, hamurah she-ba-hamurot, the absolute hardest of the hard. If it was easy, it wouldn’t need to be commanded.

In spirit and in deed, as individuals, as a community, and as a society, we must be committed to honoring our parents. It is why, as a first step, I hope this is the year our community adds a social worker to our staff family, for programming, for home visits, for help in navigating health care, to collaborate with the clergy and outside agencies. We have much work to do as a community.

But the real question, the question Heschel spoke of, is not about physical sustenance, but spiritual – not about giving materially, but about giving meaning. There is another word used in reference to filial obligation, and that is yirah, meaning reverence – as in these Yamim Nora’im, these days of reverence or awe. Ish imo v’aviv tira·u, one shall revere one’s mother and father,” states Leviticus. And what is clear here is that of utmost concern to the rabbis was not who was going to foot the bill but making sure children in the prime of their lives attend to the dignity and spiritual well-being of the prior generation.

What does it mean to revere one’s parents? To revere one’s parents is to affirm purpose in the face of the fear of being purposeless. Reverence is attitudinal, not material. It involves being patient, it requires extending honor, it demands providing dignity. Reverence begins with gratitude – gratitude to the people who brought us into the world, who shaped us as human beings, who provided for us, who put our needs before their own, who sat at our bedsides even as we now sit at theirs. Reverence involves letting things go, forgiving frequently and freely, keeping our mouths shut, setting our egos aside, subsuming our own wants for those of a person whom we can never repay. Reverence calls on us to concede that we do not know everything about everything, that – as Heschel tells us – there is much we can learn from someone “rich in perspective, experienced in failure, and advanced in years.” The greatest gift you can give someone is to ask them for their opinion. Reverence reminds us of the importance of hugs, the importance of staying connected, of nurturing intergenerational dialogue, even when – perhaps especially when – that dialogue is one directional.

Reverence calls on us to realize that there was a time when our parents were our age and there will come a day, please God, when we will be theirs. People might get older, but the image of God, as Heschel taught, remains constant. To revere one’s parents means that we treat each and every day that we and our parents inhabit this world as a gift, an opportunity to imbue their lives and our own lives with significance. Reverence reminds us that holding on and letting go, painful as they may be, are acts of love, part of life, and can go hand in hand.

Reverence for parents, mind you, has nothing to do with whether our parents are living or deceased. Each one of us is created in our parents’ image. Our values, priorities, and commitments are a reflection, extension, and sometimes a reaction to theirs. Today is Yom Kippur, as good a day as any to assess our reverence for those who came before. I put it to you. Have you stepped up to live in the image of your parents? Are you taking your rightful place in your family, in your community, in this congregation, or are you riding on the coattails of those who preceded you? I can think of no greater way to give a parent purpose, presently or posthumously, than to instantiate their concerns and commitments. I can think of no better way to demonstrate reverence for a parent than by living a life that aspires toward their ideals.

What does reverence for a parent look like? The Bible provides us with the aspirational image of an aging olive tree surrounded by the saplings it has seeded. Banekha k’sh’tulei zeitim, your children should be like olive saplings. (Psalms 128:3) In other words, a person should live to see the fruit of their labors with their children surrounding them, protecting them from the elements, providing them shade, honoring them and revering them, even as new saplings are being planted. With all due respect to Mark Twain, if we as a society, as a congregation, as sons and daughters, do our job right, a deeply fulfilling part of life could be towards its end.

Every day a Jew is instructed to recite aloud the Sh’ma – our central declaration of faith, and then, beneath our breath, we whisper, Barukh shem k’vod malkhuto l’olam va·ed, blessed be the name of God who reigns for eternity. Only one day a year – today, Yom Kippur – do we say those hushed words out loud. Why do we do so? The Talmud relates that when our patriarch Jacob, now renamed Israel, went down to Egypt to be reunited with his sons, his greatest fear was that God’s call to his grandfather Abraham and to his father Isaac would come to an end with his passing. Israel saw his grandchildren living outside the Promised Land. He saw that they looked like Egyptians; he heard them speaking a foreign tongue. Who could blame him for fearing that his life’s work was all for naught? He saw his love of the Land, love of God, love of the Jewish people all coming to an end. “Al tashliheini, do not cast me off,” we imagine him thinking as he gathered his family around him.

And, the Talmud goes on, at that moment, when Israel was on his deathbed, as his soul was being placed in God’s care, his children, his grandchildren and perhaps even his great-grandchildren stood at his side and affirmed Sh’ma Yisrael – hear, oh Israel; Adonai eloheinu – Your God is our God; Adonai ehad – God is one. As if to say, “Listen, Israel/Dad/Grandpa, you taught us well. We get it, we got this. The things you lived your whole life for, not only are we grateful for them, but we promise they will extend well beyond your lifetime. In fact, they are already being lived by your children and grandchildren today. How do we know? Because you made it so.” And with that the great patriarch closed his eyes, crossed that narrow bridge, touched eternity, and with his final breath he said aloud: “Barukh shem k’vod malkhuto l’olam va·ed, Blessed be the name of God who reigns forever.” (Babylonian Talmud, Pesachim 56a)

Today is Yom Kippur. Today we name the shared fear of being cast aside. We gather in synagogue on this sacred day just as Jacob’s children gathered at his bedside. The test is one and the same. Will we honor those who came before? Will we revere them? Will we affirm the commitments of their lives in our own? Are they assured that their values will extend beyond the length of their years? The answers to all these questions are in our hands. May we step up to the calling of this sacred day – giving meaning and purpose to the lives of those who gave us life, meaning and purpose to our own lives, and meaning and purpose to the lives of the generations to come.

Brooks, Arthur. From Strength to Strength: Finding Success, Happiness, and Deep Purpose in the Second Half of Life. Portfolio, 2022.

Heschel, Abraham Joshua. “To Grow in Wisdom.” In The Insecurity of Freedom: Essays on Human Existence. New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux, 1966.

Silverstein, Shel. "The Little Boy and the Old Man." In The Light in the Attic. New York: Harper & Row Junior Books, 1981.