On Rosh Hashanah, I shared much about the vision, the writings, and the achievements of Theodore Herzl – the founder of political Zionism. Today, on Yom Kippur, as we turn our attention to Yizkor, I want to offer a different, slightly more human version of his brief life and extraordinary career.

The version I shared last week is the stuff of Zionist histories and Hebrew School curricula. Herzl, an assimilated Viennese Jew, was sent to cover the 1894 Dreyfus trial in Paris. Bearing witness to the antisemitism of the crowds, he experienced what we would call an “aha moment,” realizing the need for a Jewish state that would cure the world of its antisemitism and rehabilitate the Jews from their exile mentality. Over the next ten years, Herzl’s life took on a frenetic pace, from congress to congress, publication to publication, meeting with anyone he could in order to forward his vision. Perhaps due to the pace Herzl kept, perhaps due to his heartache over the debates on the Uganda Plan, a sudden and fatal heart attack in 1904 felled this giant of a man mid-stride at the tender age of forty-four.

That story is the stuff of legend – a tale worthy of Zionism’s founding ideologue – heroism wrapped in tragedy. It is a story that, until I sat down with the historian of Herzl, Gil Troy, in Basel in August, I believed to be the truth. What Troy shared with me, what he will share in his soon-to-be-published book on Herzl, is that there is more to the story – much more. The flurry of activity that characterized Herzl’s life and, ultimately, his legacy, was prompted by forces far more heartfelt than merely his prescriptive recommendations for the Jewish People.

As Troy explains it, having been trained as a lawyer, Herzl barely lasted a year as a low-level civil servant. To pay the bills, he turned to journalism, something he was good at, but his head was elsewhere. He was a dreamer. His passion was in writing literary projects and plays – none of which, truth be told, he was very good at – none of which ever caught on. His marriage, which served to stabilize his finances, was loveless and troubled, his wife suffering from mental illness, their children perhaps the only thing that kept them together. His best friend, Heinrich Kana, killed himself in 1891; Herzl’s beloved and only sister Pauline had died suddenly years earlier.

As for Herzl himself, Troy explains, he lived for years with a foreboding awareness of his own impending death. Diagnosed with a heart condition in his thirties, Herzl suffered from chronic heart palpitations. At thirty-six, he had already written his will, explaining in his diary: “It is proper to be prepared for death” and “I always feel the future peering over my shoulder.” Not only, says Troy, was there nothing sudden or unexpected about Herzl’s death, but an appreciation of Herzl’s life requires that we consider that the reason Herzl wrote and worked like a man running out of time was that he knew that he was. He was a man who felt the Angel of Death hovering above. As Ernest Becker explained in his 1973 book The Denial of Death, it is the awareness of our inevitable death that is the prompt to building character, culture, and legacy. Awareness of his mortality was not Herzl’s only motivation; the last seventy-five years of Israel’s existence are testimony to the prophetic aspect of Herzl’s vision. Troy’s point is simply that there was more at hand than Herzl’s political intuitions. He was acutely aware of the finite and indefinite length of his lifetime. His passion, his pathos, was prompted by this awareness and thus his insistence to use every second, to leverage every moment of his fleeting life to build something that would outlast him.

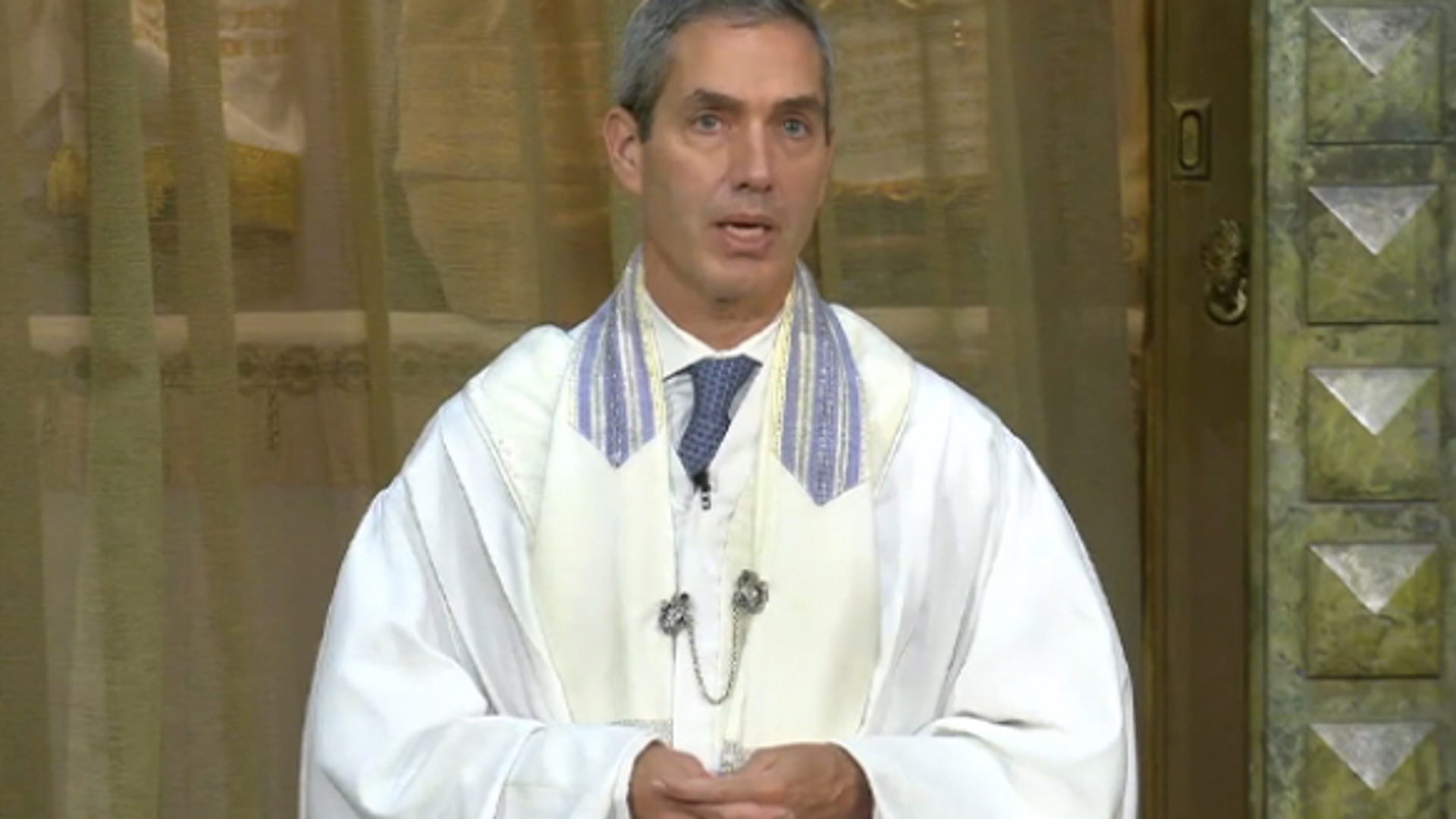

When we arrive at Yom Kippur, but really when we arrive at this moment of the Yizkor service, we are acutely aware of the finite and indefinite span of our own lives against the expansive backdrop of eternity: the generations who have gone before, the generations who will follow. Our High Holiday prayer book makes it explicit: We are but “a passing shadow, a fading cloud . . . a vanishing dream, but you, O Lord, are ever-present, enduring forever.” In the hands of the romantic, it is the juxtaposition between the passions of the moment and the eternity of the grave that gives life to every great love song and poem. In the hands of the purpose-driven soul, religious or not, it is the juxtaposition between our fleeting lives and the length of eternity that sharpens our vision, focuses our mission, and situates the calling of the day. As the futurist Ari Wallach has recently written, the kittel, the white robe worn on the holidays, which is also worn at burial, is meant to remind us of our mortal condition. It has no pockets, as if to remind you that you can take nothing with you. We enter this world bare, and we leave it bare. The only question is what we will leave behind for future generations.

Which is why, at least in part, I believe we come together for Yizkor. At Yizkor we are reminded that we are who we are because of those who came before us, those who gave of themselves so that we can be here today. One’s deeds never occur in a vacuum; they have implications for the generations to come. The prayer book teaches us that God judges us not on the merit of our deeds alone, but also on the merits of our ancestors. So too, on the other side of the ledger, merciful as God may be, the sins of one generation can be visited upon the next – not an insignificant thought as we consider the responsibilities one generation has to the next in our ecologically fragile world.

Some are granted length of years, some are not. Some pass from this world having been granted ample time to prepare, most do not. But no matter the length of our years, to be a Jew is to understand our lifespans as part of a much longer generational tapestry. We are indebted to those who came before, we are obligated to those who will come after. Human as it may be to be biased to our own lifespan, to care only about our own length of years, as Jews we know that the driver for our behavior is what Wallach calls “transgenerational empathy,” a long-term view that seeks to understand our own role in and responsibility for the lives of those who will follow. As the saying goes: “A society grows great when old men plant trees in whose shade they will never sit.” The tragic tale of Herzl’s life is instructive because it exemplifies the reality that we all know to be true but rarely acknowledge and actualize in our own lives. Our time is short, our length of years uncertain – as both descendants of past generations and ancestors to future ones, how shall we use our time?

So let us recall our loved ones – fathers and mothers, brothers and sisters, sons and daughters – those granted length of years and those taken far too soon. We loved them in life, we mourn them in their passing. We use this time to reflect on the example of their lives and the memories that we hold dear. We identify the trees that they planted in their lifetimes whose fruit we enjoy today. Perhaps it is something specific – the family they built, a passion of theirs that you maintain, a commitment they held close that you continue to this day. It might be something a little harder to identity – an aspect of their character, a manner in which they lived that you now seek to make part of how you live. The other day I was speaking to friend about his late father, and he shared that his life path could not be more different than his father’s, but every day he strives to greet each person he meets with the warmth, the humanity, and the kindness that his father showed to all in his lifetime. I cannot think of a better way to use this time of Yizkor than to consider the trees planted for us by others, whose fruit we enjoy, beneath whose shade we presently sit.

And if you have time, if you are inclined to do so, I encourage you to think not just of the trees planted long ago, but about the seeds you are planting today. Ask yourself whether, given the limited length of years we are all granted, you are living with empathy for future generations. After all, one day – please God a long time from now – our names will be spoken at Yizkor, the choices we make now shaping whether we ourselves will be remembered for a blessing.

Of all of Herzl’s diary entries I read this summer, there is one that I hold onto, that moved me more than any other. It was not political; it was personal. Herzl describes that as the Zionist Congress was called to order, he felt the history in the making, the electricity in the room, and the feeling as he was elected president of the movement that would one day give rise to the Jewish state. Notwithstanding the historical significance of the moment – or perhaps because of it – at that precise moment, sitting at the presidential table, Herzl took out five postcards and wrote notes to his parents, to his wife, and to each of his three children. It was at that precise moment that Herzl chose to express gratitude to those who gave him life, and it was at that precise moment that Herzl thought about those whose lives would follow his. That is what Yizkor is all about.

The great sage the Baal Shem Tov once explained that life itself is like a postcard. When one begins to write, one does so in large script, believing one has all the room in the world. Soon enough, however, one comes to realize that the space is limited, and so we write smaller and smaller, as we try to cram it all in.

Yom Kippur reminds us that the postcard, the canvas of our lives, is never as large as we would like to think it is. There is always more to be said; there is always more to be done. And yet limited as the postcard may be, ultimately it is meant to be sent to someone else. Always, and especially at this moment of Yizkor, we note that which we have received. As they did in their lifetime, we draft and craft our lives as best we can, from strength to strength, from generation to generation – their memories a blessing, and, please God, one day ours as well.

Herzl, Theodor. The Complete Diaries of Theodor Herzl. Edited by Raphael Patai. Translated by Harry Zohn. New York and London: Herzl Press and Thomas Yoseloff, 1961.

Wallach, Ari. Longpath: Becoming the Great Ancestors Our Future Needs. New York: HarperOne, 2022.