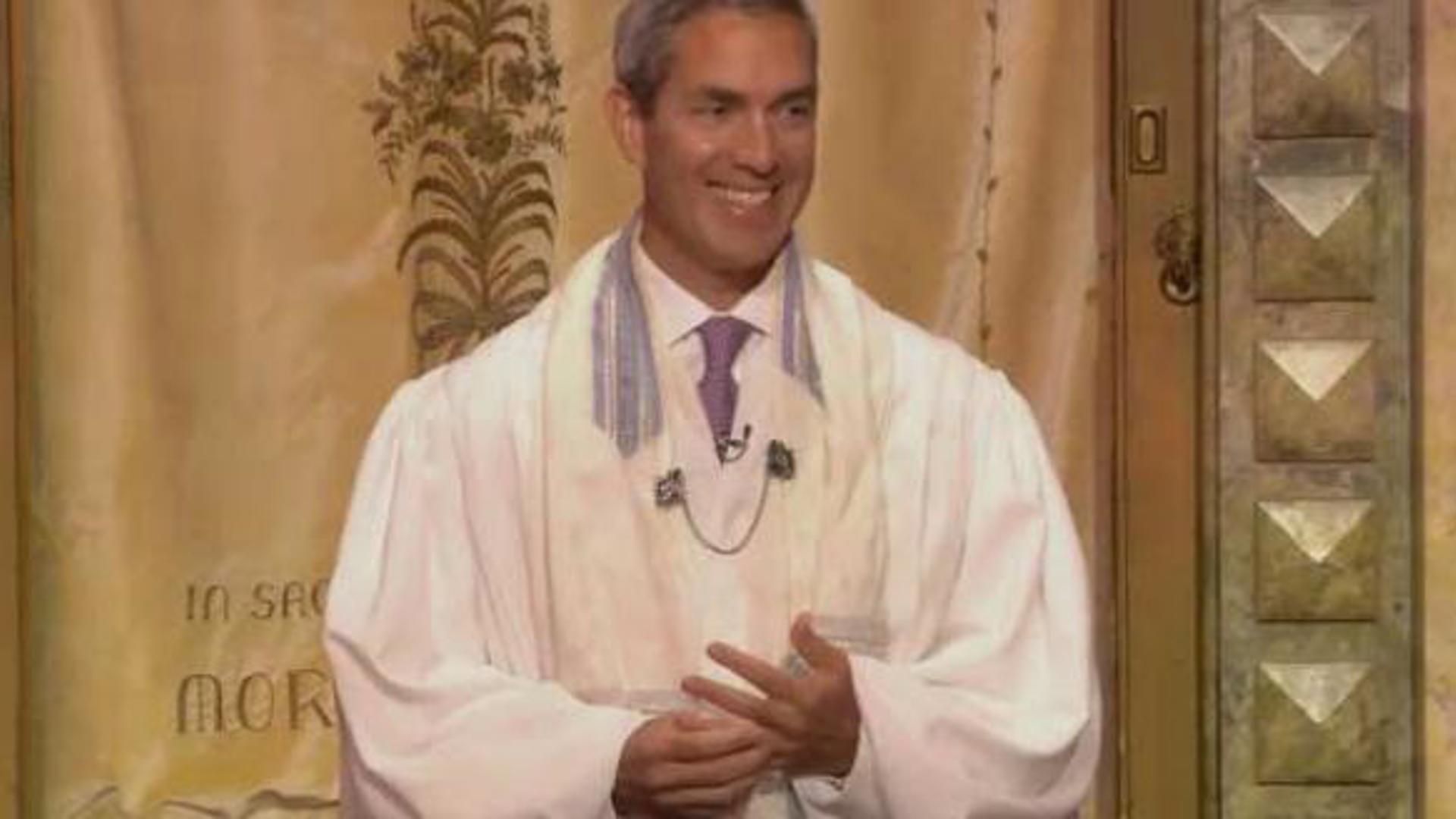

Don’t just take my word for it, or that of his parents, when I tell you that Sam Heller, a proud product of Park Avenue Synagogue, is the kind of young man you would be honored to call your own. Sam is a rising senior at Northwestern University. A journalism major, Sam landed a coveted internship at the Chicago Sun-Times this past summer. He was off to a great start, publishing a few pieces on workers’ rights, the plight of undocumented spouses of US citizens, and – my personal favorite – a deep dive into anticipated upgrades in Amtrak’s meal service. On July 8, Sam was on assignment to Chicago’s South Side to cover a press conference on Chicago’s bike sharing program when his life changed instantly and forever. Driving home to write his story, Sam heard shots fired in the distance, but by the time he could register what was going on, a stolen U-Haul van T-boned the passenger side of his compact blue Mitsubishi. Sam’s car spun out of control at the intersection of Roosevelt and Independence; the airbags blew out, and the ambulances arrived within minutes.

Sam’s car was totaled. Miraculously, he walked away just with bruises from the seatbelt that saved his life. Nevertheless, as per protocol, the hospital performed a CAT scan. Thankfully, there were no signs of concussion, no signs of internal bleeding, but there was something. The doctors decided to keep Sam overnight for an MRI and observation. The following day, and by now Sam’s folks had arrived from New York, the family was informed that a brain tumor had been found. It had been there a long time, growing larger over the years, but Sam had no symptoms; he never knew it was there. The family flew back to New York and, having been presented with the medical options, decided to operate immediately. It’s a good thing they did. The tumor turned out to be even larger than the scans had indicated. Left undiscovered, the first symptoms would have been crippling seizures, followed by far more perilous surgery, with the remainder of Sam’s life under medication and constant vigilance. The surgery was successful; Sam’s recovery – remarkable. He returned home to celebrate the August 12th birthday he shares with his twin brother Ben. Every passing day he is stronger than the one before. He will have a few days of radiation in December and probably an annual MRI. Most importantly, Sam is excited to get back to school, senior year, and living his life. [Sam – it is great to see you in shul!]

Physical health aside, how does Sam feel? Well, I asked him. On the one hand, not surprisingly, he is filled with gratitude. He knows that his is a “but for the grace of God” story if there ever was one. What Sam also knows is that embedded in his story are more questions than answers. What if he had not put on his seatbelt that day? What if there had been a friend in the passenger seat, or if the car had hit the driver’s side and not the passenger side? Had he been a split second ahead, Sam might not be alive today. But then again, had he been a split second behind, if the stolen van had missed him entirely, there would have been no MRI. Had there been no MRI, the tumor would have remained undetected and there would have been no life-saving surgery – a cascade of unknown scenarios. A sequence of chance events that could have gone one way or the other, events that forever altered the direction of Sam’s life. An interminable series of impenetrable “what ifs.” Gratitude mixed with mystery mixed with dread, all prompted by the realization that our lives can be upended at any instant.

Sam’s story is a great one, but it is not just a one-in-a-million story; it is one of a million stories that I can tell, that you can tell, that we all can tell about the world in which we live. Life can change in the blink of an eye. In the abstract, we all know it to be the case, but stories like Sam’s put an exclamation point on the conditions of our existence. We are all living by a thread, seated beneath the mythical sword of Damocles. In the days ahead, we will observe the twentieth anniversary of 9/11, a date on which the entire world changed. If you are of a certain age, I imagine you can recall exactly where you were that day. I know I can. Holding Debbie’s hand as the towers fell, holding our newborn child as our sense of reality came crashing down. The horrorstruck awareness of the lives instantly lost and the unending grief of their loved ones. Depending on our generation, we remember where we were on 9/11, on Pearl Harbor, when we went into lockdown. We can replay those days of infamy in slow motion, recalling them in great detail. Less remembered are the days leading up to those days – the September 7ths, 8ths, 9ths, and 10ths. We live our lives sleepwalking, seduced into the comforting belief that how things are is how things will always be, until that seismic moment arrives and we are shocked out of our complacency. But by then the deed is done. We have no choice but to acclimate ourselves to our new reality with whiplash speed.

And, needless to say, all stories are not like Sam’s. Aside from his being a child of our congregation, what struck me most about Sam’s story was that it happened as I was absorbed in the story of another Chicago college intern – Max Lewis – about whom you may have read. A rising junior at the University of Chicago, by all accounts Max was both brilliant and an incredible mensch. Just days before and blocks away from Sam’s accident, Max was commuting home from his internship on Chicago’s Green Line when a stray bullet ripped through the window and struck him in the neck. For Max and his family, there would be no redemption. Max died three days later. A beautiful young man deprived of length of years, his parents given the unimaginable task of burying a child. In thinking of Max, I cannot help but consider the same sort of questions as I did with Sam. Had Max returned one more email before leaving the office that day. Had he taken a different seat in the train. Had he bent down to tie his shoes or check his phone or if the train was going a touch faster or slower – or, or, or – Max would still be with us. You can’t have it one way and not the other. For every Sam, there is a Max. For every person who was supposed to be in the North Tower or the South Tower or the Surfside Tower but miraculously wasn’t, there was someone who might not have been, but tragically, was. For every CAT scan bearing good news, there is one bearing bad. Our world comes with no promises, a cauldron of chaos that can bubble over at any moment – the trajectory of our existence redrawn at any time.

Today is Rosh Hashanah. Hayom harat olam – tradition teaches that this is the day the world was created. And yet this year, it is not so much the order of creation that we feel, but the disorder, the disarray and, yes, the chaos. Good as God’s creation may be, the very first verses of Genesis assert that our world was established on a foundation of tohu va-vohu – a howling and empty void. The great Bible scholar of our time Jon Levenson argues, as did the Midrash long before him, that the biblical story of creation is meant not merely to describe God’s hand in fashioning a majestic universe, but to draw attention to God’s ongoing efforts to keep the levee from breaking, to tame the flood waters of chaos that are ever seeking to burst forth. It is a story about disorder, anarchy, and the persistence of evil. A world both random and erratic – a world that can be upended in any place, at any instant. By this telling, today, Rosh Hashanah, is not so much a day to sit back and breathe in the wonders of providential design, but a day to sit up, take note, and ask ourselves how best to navigate a world that is shot through with contingency.

If there was ever a year in which we are attuned to the Chaoskampf built into creation – then this is the year. Pandemic, war, hurricane, flood, fire, earthquake – there is something so very biblical about our moment. Every conversation, every plan, every email, every budget, every sermon, every everything comes with a built-in contingency. Will we be working from home or the office? Will school be on campus or online? Will High Holiday services be in person or virtual? How bitterly fitting is this Delta variant named: delta, the Greek letter denoting “change.” Everything is changing all the time. In retrospect, last year, in all its horribleness, was more straightforward. What can be more straightforward than a lockdown? This year, everything is in flux. My heart has been broken, again and again, for our children, for my children, who are trying their level best to put one foot in front of the other. We all feel it – I know Debbie and I do – two years in a row with a child spending Rosh Hashanah isolating in quarantine on a new campus. And were it just quarantines, cancelled graduations, and rescheduled weddings, that would be difficult enough, but it is far more. It is the not knowing when one will launch their love life or professional life, the not knowing when one will see a loved one again, the not knowing if our democracy will survive, the not knowing if there will be a habitable planet for our children and children’s children to live on. It is not just that our lives have been thrown off course; it is that we have become totally unconvinced about our tomorrows. And it has taken a toll. When you aren’t sure about what comes next, when this world, like Lucy to Charlie Brown, keeps snatching the football from under us, is it any wonder that the incidence of anxiety, depression, substance abuse, and suicide are on the rise? The target keeps moving, and we are forced to recalibrate and recalibrate – again and again. It is destabilizing, it is exhausting, and it begs the question of how we, mere mortals, can contend with a world that is at worst governed by chance and at best by a Will whose wisdom will forever lie beyond our grasp.

And . . . it is a state of affairs that speaks to the calling of today.

For as long as human beings have been human, we have known that our lives are of limited and indeterminate length, that we can be here one day but not the next. Isn’t that the point of the central prayer of these High Holidays – U-netaneh tokef? Who will live and who will die? Who by fire and who by flood? Who by earthquake and who by plague? Aside from noting how eerily up-to-date the ancient categories are, we would do well to consider the phrasing of the prayer. Nobody knows the who, the how, the when, and certainly not the why of our tenure on this earth. All our lives can turn on a dime – sometimes for the better, but often for the worse. It is the theme that links all the Torah readings we encounter over the holidays. Sarah blessed with child after years of being barren. Hagar cast into the wilderness and then saved at the last second. This year we are all Isaac bound on the altar, unsure if the angel will arrive in time or at all. The cast of characters in our Torah and Haftarah readings are individuals, no different than all of us, forced to pivot over and over. The effects of Covid may have put a spotlight on the chaotic nature of our existence, but the fickle nature of existence is a truth that these Days of Awe call on us to confront every year.

The realization that life can come and go in the blink of an eye, that there is an instability built into our lives, can undoubtedly drive a person to nihilistic despair. But the theological calculus of the High Holidays is very explicit. Life is precious, existence is unstable, so personal agency is everything. Who will live and who will die? No idea. But we can live our lives making each day count; we can live with the desperate intentionality that the world could be upended tomorrow. Being aware of the fragility of existence does not render us powerless; it can empower. We can infuse life with meaning, living in a manner that reflects awareness that our next day could be our last.

The High Holiday prayer book teaches us that we can take on personal agency in three specific ways: acts of teshuvah/repentance, acts of tefillah/prayer and acts of tzedakah/righteous giving.

Let’s start with teshuvah. Literally, it means repentance – the act of seeking and granting forgiveness for the missteps of our lives. More broadly, it signals the state of disrepair that many of our relationships are in – sometimes due to wrongdoing, but oftentimes, to benign negligence. One of the most modest and moving exchanges of my past year was when I mustered the courage to tell someone whom I love very much, who I know loves me, that I feel like I am always the one picking up the phone and putting in the effort. For years I had squirmed over whether to have the conversation. When I finally did, the guy was grateful for my candor, responded with warmth, explained he had no idea, and now he calls me every week. [If you are watching, take the week off for goodness’ sake! I have a Yom Kippur sermon to write . . . but I do love your calls.] Not every act of repentance has to do with some colossal treachery or betrayal. Some do, but more often than not, we just need to be more diligent in relationship maintenance before something really goes wrong. Acts of teshuvah need to be done with urgency given that we do not know what tomorrow may bring. In the Talmud, Rabbi Eliezer urges his students to perform teshuvah one day before their death, to which his students understandably respond, “But how can anyone know the day of their death?” Rabbi Eliezer clarifies that a person should live their entire lives in a state of teshuvah. (Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 153a) What is the first lesson of these holidays? Life is short. Get your relationships in order: Go for a walk, go for a talk, pick up a phone. It’s what these days are about. Don’t wait. Tomorrow may be too late.

Second, tefillah. The Hebrew word technically means prayer but can be more broadly defined as spiritual living. What defines a life of meaning and purpose? How am I connected to those who came before me, and what is my legacy to those who will follow? How do I balance the particularism of my Jewish identity with my universal commitments to a shared humanity? What is it that God requires of me?

One day I will teach a class about my favorite philosopher, the man who, aside from Moses, shaped my intellectual passions: the sixteenth-century philosopher Michel de Montaigne. Montaigne was busy going about his life when, to put it mildly, he hit a rough patch. His father had died young; he lost his younger brother to a freak sporting accident – a tennis ball hitting his head. His first child died at two months, and he would in time lose four of his six children. His best friend, Etienne de La Boetie, was killed by the plague, and he himself was racked with the piercing excruciations of kidney stones. Death was no nebulous abstraction for Montaigne. In 1560, he was flung off his horse and as he lay on the ground throwing up clumps of clotted blood, Montaigne sensed himself slipping into death. But Montaigne neither died nor gave up. He started paying attention, and he wrote. He wrote not about how to die but how to live – how to love, to laugh, to learn, to weep, to mourn, and so much more – essay after essay on the subject of living. The word “essay” actually comes from the French essayer, meaning “to try.” We die, yet we try. It’s a little kitschy, but not an inaccurate summation of these holidays.

And for those of us who are not great essayists or philosophers, we can make this year the year to elevate our spiritual living – one mitzvah at a time. I have spoken about the importance of taking on a life of mitzvot many times. Get used to it. I intend to do so as long as I have the mic. While there are all sorts of reasons to observe mitzvot, to connect to God, to connect to Jews and Judaism, let me suggest another. To put on tefillin, to observe Shabbat, to refrain from eating certain items on the menu – these are all bold assertions of personal agency in the face of a world beyond our control. Don’t misunderstand me: mitzvot are not some coping mechanism in the face of chaos. Rather they are annual, seasonal, weekly, and daily reminders that every moment can infused with meaning, with purpose, and yes, with sanctity. I promise you faithfully that when the Cosgrove family sits down to light Shabbat candles, the mood is anything but pristinely calm. One kid is yelling at another for taking their sweet time in the shower, Debbie is wrapping up yet another phone call with yet another sibling, and I am desperately trying to finish all my Shabbat preparations. But then that magical moment comes when we light the candles and push out the bad and bring in the good, making a daring unspoken assertion: In the midst of the chaos, every deed matters and every moment can be made sacred. “Do not say,” taught the ancient sage Hillel, “when I have time to study Torah, I will study – for you may never have time.” To live a life of mitzvot is to strive spiritually to use the historic and ever-evolving Jewish toolbox to explore the existential questions we all have in our hearts.

Which brings us to the third and final High Holiday expression of personal agency – tzedakah. It is often translated as charitable or righteous giving, but it can be expanded to include the degree to which we insist that our own deeds impact this world in which we live. Why was Abraham chosen to be the founder of our people? The Rabbis compare him to a man on a journey who sees a birah doleket, a palace ablaze in flames. The traveler wonders if it is possible that the palace lacks an owner. Just then, the owner of the palace calls out from the blaze, “I am the owner of the palace,” and the traveler understands their own duty to help extinguish the fire. Abraham, and by extension every Jew ever since, is called to respond to our world in need of rescue and repair, to put out fires wherever in God’s world they are ablaze.

To live a life of tzedakah means that when we see something, we don’t just say something: We do something. The effects of this pandemic have been described as the letter K, with a few winners on the upward path and far more suffering on the downward path. If you are in a financial position to impact local agencies, national conversations, global initiatives, and yes, Jewish life, but have yet to do so, then I ask you: What exactly are you waiting for? This is no Rabbinic parable: Our world is quite literally on fire! The heroes of our people, past, present, and future, have been those individuals who have leveraged whatever means are at their disposal to bend the arc of the universe towards justice. Tzedakah, righteous living, is about money, policy, and politics but it is not just about those things. Giving back is not only the purest expression of gratitude for the blessings of one’s life; it also demonstrates the belief that from the moment we wake up to the moment we sleep, we have only a finite amount of time to actualize our ideals. We do so because it is the right thing to do; we do so because it sets an example for our children and inspires the community around us to do the same. Most of all we do so because we are all here for but a flash. No one knows what tomorrow will bring, and no one gets out of this one alive . . . so live your life as if it matters.

Friends, I pray that the year now beginning brings peace, blessing, and calm, but I can’t promise it; none of us can. To be a rabbi, to be a pastor, is to live with a profound and pounding awareness of the precious and precarious nature of life.

Indeed, when I spoke about Max Lewis to my colleague, the Hillel rabbi at the University of Chicago, she reminded me of what I had read in the news, that Max did not die immediately. Struck in the neck by a bullet, Max was rushed to the hospital, and though he regained consciousness, having suffered a high spinal cord injury, he couldn’t talk, he couldn’t use his arms or legs, he couldn’t eat, and he couldn’t breathe except with a ventilator. For communication, a speech therapist came in with a letter board. Max could only move his eyelid – one blink for “yes,” two for “no.” The doctors explained to Max the severity and irreversibility of his condition; this would be a matter of “when” not “if.” His friends prayed outside his room as his family stood at his side. One blink at a time, Max communicated to his mother by means of the letter board. “I’m ready to die. I’m ready to go home. Please pull the plug. I can’t live this way.” The Sh’ma was recited. Max’s final act in this world was the empowered choice to determine the terms of his death.

A blink of an eye – that’s all it takes – the difference between life and death. The question we face today, however, is not how we want to die but how we want to live. Each one of us can endeavor to make empowered choices regarding the terms of our existence. To live with urgency, intensity, agency, and joy – yes, joy – in accordance with the fleeting, indeterminate, and precious nature of the gift of life. To laugh, to love, to give, to forgive, to learn, and to do – for ourselves, for those no longer with us, and most of all, for those whose lives are yet to come.