In retrospect . . . those college students . . . they never stood a chance.

The time was late fall of 1949, and the place was a narrow, dimly lit hallway at 770 Eastern Parkway, the Brooklyn headquarters of the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzhak Schneersohn, by then too frail to go beyond his quarters. Two young men, Shlomo and Zalman, both in their twenties, sat outside their ailing leader’s room, singing gentle niggunim, wordless Hasidic melodies, which like the young men themselves, were remnants plucked from the ashes of a European Jewry destroyed in the Holocaust just a few years before. (Samuel Heilman, The Rebbe: The Life and Afterlife of Menachem Mendel Schneerson, p. 168)

The Rebbe’s door creaked open and the Rebbe’s secretary whispered: Der Rebbe ruft eikh, “The Rebbe is calling you.” The young rabbis were escorted in, directed to sit at the table of the Rebbe, who nodded approvingly as three glasses of schnapps were poured. A blessing was made and the schnapps . . . sipped in silence. Moments passed, and then the Rebbe turned to the young rabbis and uttered seven Yiddish words that would set in motion a revolution, a revolution that continues to this very day: Keday ir zolt onheybn forn tsu colleges. “It would be worthwhile for you to start visiting the colleges.” America, the Rebbe explained, is a wonderful place – a haven of comfort and security for the Jewish people. But six million Jewish souls had perished in Europe, and now a new generation was being born in America, a generation whose souls were in danger of being lost, whose souls must be saved. “Go bring them close,” instructed the Rebbe as he handed them the bottle of schnapps. Keday ir zolt onheybn forn tsu colleges. “It would be worthwhile for you to start visiting the colleges.”

In the days to follow, the two young men got hold of an old Plymouth and drove in the direction of Boston. They brought with them 13 pairs of discarded tefillin, a few recordings of Hasidic music on reel-to-reel tapes, and some pamphlets of the Rebbe’s teachings. Their first stop was Brandeis University. It was Hanukkah, and they made their way to a holiday party, with jukebox playing, in the Castle – the then student union. The two men entered, and the room turned silent as they set up their accordion, tefillin, and materials. In one corner, the young Shlomo began to sing as he fielded questions from the students. In another corner, Zalman spun Hasidic tales while inviting the students to wrap tefillin with a promise to give a pair of tefillin to anyone able to put them on and take them off three times. Those Brandeis students . . . they didn’t know what hit them; they never stood a chance. Those two men were not just any men. Shlomo was Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach – the man who would over the course of his lifetime (notwithstanding his personal failings) revolutionize the canon of American Jewish music. Zalman, his friend, was Rabbi Zalman Schachter (later Schachter-Shalomi) – the founder of the Jewish Renewal movement, one of the most creative Jewish minds of the twentieth century. The students hung onto the rabbis’ every word and sang every melody. By dawn, thirteen pairs of tefillin had been handed out, thirteen Jewish lives transformed by the performance of a mitzvah. A Hanukkah – which means rededication – to remember. American Judaism would never the same. (Aryae Coopersmith, Holy Beggars: A Journey from Haight Street to Jerusalem)

Soon after that historic Hanukkah, the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe passed. His charge to Shlomo and Zalman one of his last directives to his students. A year later, on the occasion of his first yahrzeit, Menachem Mendel Schneersohn was appointed the seventh Lubavitcher Rebbe and, at the farbrengen marking the beginning of his leadership, he gave voice to the vision and mission going forward. In Schneerson’s words: “One must go to a place where nothing is known of Godliness, nothing is known of Judaism, nothing is even known of the Hebrew alphabet, and while there, put one’s own self aside and ensure that the other calls out to God!” (Joseph Telushkin, Rebbe: The Life and Teachings of Menachem M. Schneerson, The Most Influential Rabbi in Modern History) In the years ahead, the Rebbe would dispatch emissaries across the country and globe, on street corners, mitzvah mobiles, and otherwise – campaigns (mivtzaot) encouraging tefillin, Shabbat candles, kashrut, Torah study, tzedakah, mezuzah, mikveh, among other mitzvot. What was for Rabbis Carlebach and Shachter an impromptu act of outreach would become, in the hands of Schneerson, a worldwide campaign.

This fall marks seventy years since that fateful evening of outreach and twenty-five years since the death of the Lubavitcher Rebbe. It would be understandable if, in reviewing American Jewish life of the last seventy years, one were to overlook the profound achievements of Chabad. In the decades since the Shoah, our people, thank God, have had our share of success stories, including synagogues like our own, the Hillel movement, Jewish camping, Birthright trips, Holocaust memorials, Jewish studies departments, and the greatest success of all – the State of Israel. Chabad is perhaps the most unexpected player in the landscape of American Jewish life. From a cultural curiosity in the nineteen forties and fifties, Chabad has blossomed into a vast and dynamic and ever-growing network. With over three hundred Chabad Houses on campus and five thousand sheluchim/emissary families, Chabad can boast a foothold in all fifty states, not to mention a formidable online presence. Simply put, the last seventy years of American Jewish history could not be written without mention of Chabad’s manifold achievements.

And at the core of it all, the spark that got it all going is one word – mitzvah. An all hands-on-deck, non-judgment pass, full court press, to have as many Jews as possible perform as many mitzvot as possible. Chabad’s mitzvah campaigns are not, by any stretch, the only tactic of the last seven decades to revitalize Jewish life. Ultra-Orthodox communities have built enclaves isolated from the corrupting influences of the secular world. Progressive communities have assimilated elements of the non-Jewish world into Jewish practice. Zionists have walked away from America altogether, believing only Israel can guarantee the Jewish future. Chabad functions in the same landscape; they have just responded with a different tactic. The Rebbe routinely referred to the United States as a malkhut shel hesed, “a government of kindness.” He understood the blessings of our country better than anyone. But what he also understood was that such blessings came with a challenge; the challenge of how American Jews could differentiate themselves within such hospitable surroundings. Which meant that for the Rebbe, mitzvot were the key. The performance of a mitzvah, a distinctly Jewish act – tefillin, Shabbat candles, making challah, or otherwise. That is the key, the secret sauce by which the assimilated American-Jew would find his or her way back into yiddishkeit.

Before I say another word, lest you be wondering, I am not outing myself today as a Chabadnik, and Park Avenue Synagogue is not turning into a Chabad House. But with regard to the performance of mitzvot – distinct and differentiated Jewish deeds – on that front there is no daylight between me and my Chabad friends. Schneerson was right about the direction of American Jewry in ways that even he didn’t imagine possible. We live with freedoms the likes of which prior generations could only have dreamt about. An upwardly mobile community that enjoys hard-earned political, social, and economic blessings. An American Jewry who live in unprecedented comfort with regard to antisemitism. An American-Jewry who, by dint of the efforts of our brothers and sisters across the ocean, are living in the era of the longest period of Jewish self-sovereignty in 2000 years. It’s not that we don’t have problems – of course we do – but the problems American Jews face are, by and large, the high-class kind – derived from the blessing of having options, of having power and privilege, of being accepted and loved by our non-Jewish neighbors. If I had to choose the problems of any Jewish generation throughout history, hands down I would choose ours any day of the week.

But what is good for Jews is not always good for Judaism.

The philosopher Ernst Renan once explained that a people is sustained by the shared memory of a past and the willingness to continue that heritage as a common possession. The unintended consequence of the blessings enjoyed by American Jews, of our acceptance by this malkhut shel hesed, is that our collective memories, our common bonds and shared language, have withered. The crisis, however, runs deeper. The fact of our freedom, after all, is not new – Schneerson understood it well seventy years ago. What is new, what our generation must contend with that past generations never did, is the fraying of our unspoken safety net, the three things that rightly or wrongly American Jews could count on to keep us together, but can do so no longer: 1) The Shoah, 2) Israel, 3) Antisemitism.

First, the Shoah. When I went to Hebrew school, I was taught about the 614th commandment – that in addition to the 613 commandments, after the Holocaust there is an additional commandment – to remain Jewish lest we provide Hitler a posthumous victory. But more important than what was being taught, was who was teaching: Hebrew School teachers with concentration camp numbers tattooed on their arms. Seventy years later, our commitment to the memory of those murdered in the Shoah remains resolute and eternal. But for Jewish educators, it is neither practical, nor for that matter, conscionable to leverage the horrors of the Shoah to prompt positive Jewish identification in the next generation. The Shoah can no longer be counted on to inspire individual or collective Jewish identity.

Second: Israel. For seventy years, Israel has been the centripetal force keeping American Jews together. In ’67, ’73, Entebbe, Osirak, in triumph and tragedy, Israel has brought us close. But you and I both know that for the coming generation that is no longer the case. Israel alienates as many American Jews as it engages. Ours is an era where our opinions regarding Israel divide as much as they unite. And as for the extraordinary success of Birthright, Honeymoon Israel, Onward Israel, and all the other Israel programs that you should support and send your children and grandchildren on, none of them answer that question of how and why to live an engaged Jewish life once you return from Israel to America. Israel can no longer be counted on to inspire individual or collective Jewish identity.

Third: Antisemitism. Notwithstanding the hatreds about which I spoke on Rosh Hashanah, American Jewry is living in an unprecedented era of social tolerance. Say what you will, the state-sponsored antisemitism of other times and other places is simply not the lived experience of American Jewry. A blessing to be sure, but also a challenge. To paraphrase the provocative comment of the late Rabbi Arthur Hertzberg: The only thing worse for a Jew than antisemitism is no antisemitism. Why? Because then the onus for a Jew to be a Jew is on nobody but him- or herself. Besides, what sort of Judaism is it, if it is reliant on the hatreds of others in order to survive? Antisemitism can no longer be counted on to inspire individual or collective Jewish identity.

The Shoah, Israel and antisemitism. These were the three forces, the threefold mystic cord that we could always count on. Three constants that even Schneerson could fall back on to keep the Jewish people together. Three constants that are constant no longer.

Which is why we need mitzvot. Mitzvot are the chords – the commitments and commandments – the sparks that can inspire individual and collective Jewish identity. The proud performance of Jewish deeds that are not contingent on the Shoah, that have nothing to do with how we feel about Israel, and that exist independently of antisemitism. Let me be clear: I am not talking about being kind, about a nebulous plea to live according to some inchoate set of Jewish values. I am talking about kashrut, about prayer, about Torah study, about coming to shul, about tzedakah and yes – tefillin and Shabbat candles, too. I am talking about the Jewish obligation and opportunity to perform distinctly Jewish acts on your own and in the company of other Jews. I am talking about mitzvot.

There, I finally said it. It’s been more than a decade, and I am saying the very thing a rabbi is supposed to say: I am asking you to do mitzvot. You know the old story about the young rabbi who arrives at his new congregation fresh from rabbinical school. He consults with the chairman on ideas for his first sermon. He wants to talk about Israel; the chairman counsels against it, explaining that the community is divided on Israel. The young rabbi pivots and says that he will speak about Jewish business ethics; the chairman again counsels otherwise, lest the rabbi unknowingly offend a congregant. Yet again the young rabbi pivots, to the well-worn theme of lashon hara, gossip; and the chairman cautions the rabbi that that theme too would upset his chattier congregants. Exasperated, the young rabbi pleads: “I can’t talk about Israel, I can’t talk about ethics, I can’t talk about gossip; what do you want me to talk about? To which the chairman replies: “Judaism! Why not just talk about Judaism?”

The story is supposed to be a joke, only this time it is no joke, or at least the joke is on us. Over the years I have spoken to you about Israel, I have spoken to you about ethics, I have spoken to you about gossip. Today, I am talking about the thing I have avoided all these years: Judaism. The Jewish obligation and opportunity to perform distinctly Jewish acts on your own and in the company of other Jews. Mitzvot. The shared language that has kept our people together through ages; The Proustian madeleines, the triggers to memory that have kept our people together – across continents and through the generations – the sparks that have ignited the Jewish soul throughout the ages.

For the spiritually minded, mitzvot are the gestures that we make, the rituals we do to express our vertical relationship to the divine. The relationships in my life that mean the most to me – my wife, my parents, my children, defy the limitations of words. So I express those relationships in deeds, in actions – daily, weekly, and seasonally – that reflect the covenantal bonds that we share. It is simply beyond my ability to give voice to the joy of being alive and, when faced with it, the unspeakable sorrow that comes with the limits of my humanity. I have no words – so I turn to mitzvot. Mitzvot are what make the mundane sacred, the agonizing tolerable, and the presence of God palpable when I need it most and feel it least. It was Louis Finkelstein, the late chancellor of JTS, who reflected: “When I pray, I speak to God; when I study Torah, God speaks to me.” When I light Shabbat candles, when I put on tefillin every day, when I refrain from eating from one side of the menu in favor of the other; I am – to use Heschel’s language – taking a leap of action. I am giving expression to a vertical relationship to a God in heaven who exists well beyond the limitations of speech. Mitzvot are the sacred vocabulary that a Jew draws upon to express his or her relationship with the divine.

And I know, for many of us, theology is not enough; Or more precisely, it is too much – a leap of faith too far. You don’t subscribe, you say, to a commanding God, to outdated notions of reward and punishment. Instead, I encourage you to think of mitzvot not in the vertical, as a connection to a God above, but in the horizontal, a connection to your fellow Jew. The great twentieth-century thinker Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan spoke of mitzvot as folkways – the shared customs that constitute the Jewish civilization. Every community has its folkways, the behaviors and regimens – daily, seasonal, and otherwise – that make a community a community and each one of us a part of that community. Folkways that mark the passage of time and personal transformations, that connect us to a past that long precedes us and a future well beyond the horizon of our brief years. The architecture by which we build a conscious community. Why are we here in shul today? Two million American Jews, according to the Pew study, are in synagogue, fasting and praying prayers – some of which we understand, a whole bunch we probably don’t. Why? Our very presence here today signals that we intuitively understand the power of mitzvot as folkways. My only question, and I am getting ahead of myself, is whether we can extend that intuition beyond this one day.

There are all sorts of reasons to observe mitzvot, probably as many reasons as there are mitzvot, not the least of which is, speaking personally, that I quite enjoy them. Today I would ask you to consider the most basic reason of all: mitzvot as positive acts of Jewish self-identification. For many years, Jews have lived according to Yehuda Leib Gordon’s dictum of being “a Jew in the home and a man on the street” – to keep the fact of our Jewish identity hidden from public eye. As American Jews our lives are akin to story of the man on the subway reading the paper, sitting across from a lady, who staring at him intently, eventually asks: “Excuse me sir? Are you Jewish?” The man politely replies: “No.” Moments pass, and the woman again inquires: “I am sorry to bother you, but are you sure you are not Jewish?” Again, the man politely, but this time firmly, replies: No, he is not Jewish. The lady can’t help herself: “Sir, I have to ask . . . Are you absolutely, positively sure you are not Jewish?” At which point the man slaps down his paper, looks up exasperatedly, and blurts out: “You know what, lady, you are right – you got me – I am Jewish!” To which the lady replies: “Funny, because you don’t look Jewish.”

The positive and open expression of your Jewish self: that is the argument for a mitzvah. Think about the choreography; I imagine most everyone in the room has been invited to the dance at least once. First, the question: “Excuse me, are you Jewish?” And then, the follow-up. If you are a man: “Would you like to put on tefillin?” Or, if you are a woman: “Would you like to learn how to light Shabbos candles.” The question is not an “ask.” It is an offer, an invitation, perhaps even a challenge. Would you, by way of performing this distinctly Jewish act, this mitzvah, please self-identify as a Jew? Performing a mitzvah is a proud transformation of the universal self into a Jewish self, making manifest one’s particular identity by way of the decision of what to eat, how to structure one’s time, and how to present oneself to the world. Why should you observe mitzvot? Because doing so is the means by which you express pride in who you are and in where you came from and your hope that those who come after you will feel and do the same. There is no greater act of Jewish self-assertion, empowerment, and hope than the performance of a mitzvah. To do a mitzvah is to take agency for your spiritual life.

I am not a Chabadnik for all sorts of reasons. To name but a few: I have a more expansive definition of mitzvah than they do. I have a more inclusive and egalitarian definition of the Jewish people than they do. And I have a far more progressive notion of how Jewish law develops than they do. But I am your rabbi, so let’s put it out there: Can this year be the year you take on mitzvot in your life? I don’t need them all, I am an incrementalist. I believe that one mitzvah leads to another. Just don’t tell me that ritual is not your thing or that you can’t make the time. Our lives are filled with rituals: timebound, dietary, and seasonal. We go to Soul Cycle, we go to yoga, we eat GG crackers for God’s sake! We carve out time for marathons, we shlep to the new workout in SoHo, and we freeze on the sidelines of our children’s club sports in God knows where. We can prioritize just fine – when we deem something to be a priority! American Jews are full of mitzvot, just not the Jewish ones. I want you to take on the Jewish ones! I want you to take agency for your spiritual life. Mitzvot are not the sole domain of the Orthodox – they belong to all of us! Let’s give the Jewish world something to talk about – a Conservative synagogue proudly and passionately pursuing mitzvot. The great twentieth-century Jewish thinker Franz Rosenzweig, when asked whether he put on tefillin, replied “Not yet.” Let this year be the year. Here in this room, right now, take the time to reflect, reflect with your family: how can you move from “not my thing,” to “not yet,” to “why not, let’s see what happens.” “Taste and see,” teaches the psalmist. (Ps. 34:9) Be open to performing one holy deed and see what happens next. As Maimonides taught, all it takes is one deed to tip the balance in one direction or the other. (Laws of Repentance 3: 4).

And let this synagogue, my colleagues and I, guide you in your efforts. The theme of our fall programming, as announced by our chairman and as outlined in the brochure on your seats, is “rededication.” Yes – our physical building will be rededicated in time for Hanukkah. But today it is the spiritual architecture of your year ahead that is my concern and that should be yours. If you don’t know how to put on tefillin, to put up a mezuzah, to open up a prayer book, to study a Jewish text, to make your home kosher – we are here for you. My colleagues and I would love to spend time with you teaching you how to prepare a shabbat table, light shabbat candles, and say kiddush. Come to think of it, that is actually what you hired us to do! The Rebbe himself was once asked: “What is a rabbi good for?” He replied: “The Earth contains all kinds of treasures, you just have to know where to dig. If you do not, you will come up not with diamonds, but rocks and mud. That’s why you need a geologist – to tell you how and where to dig. What is a rabbi good for? A rabbi is a geologist of the soul. But a rabbi can only show you where to dig. The actual digging…you must do yourself . . .” (Z. Schachter Shalomi, The Geologist to the Soul: Talks on Rebbe-craft and Spiritual Leadership). How amazing would it be if, when we dedicate our building in December, when we light that Hanukkah menorah with candles representing the spectrum of Jewish deeds, seventy years after that Hanukkah on the Brandeis campus, you are able to reflect on your own Jewish life, dedicated and rededicated to proud Jewish living.

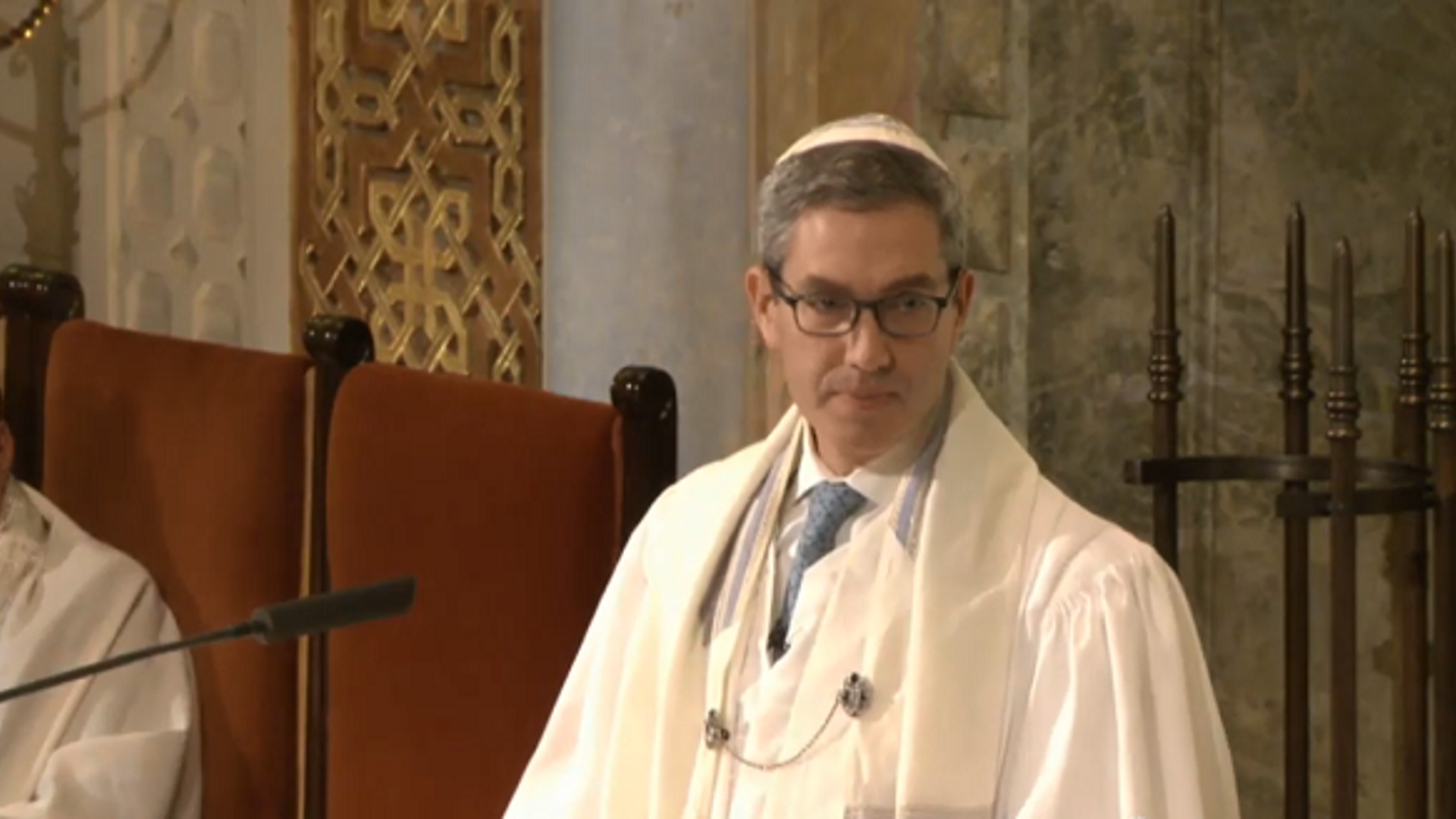

The closest Park Avenue Synagogue ever came to becoming a Chabad House was in 1966 when, under the leadership of one of my predecessors, Rabbi Nadich of blessed memory, Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach was invited to teach and sing in the synagogue for an evening. By way of the Shapiro Audio Archive on our website, I listened to a recording of that evening. I invite you to do the same after yontif.

It was a moving program, a taste of Hasidus here on the Upper East Side, an evening that concluded with Rabbi Carlebach singing Am Yisroel Chai, “The people of Israel live.” Before concluding, he spoke, and I would like to share with you what he said. He said: “You know, if I put a piece of chicken on the table, you have to chew it yourself. I can only put it on the table; you gotta work yourself. The story is told of two Hasidim from two different hevres/sects who met up. One says to the other: ‘Tell me, great rabbi, what is the most important thing to you?’ The other says: ‘The most important thing is whatever I am doing at that very moment.’” And Reb Shlomo concluded: “That is the most important thing to him. That means he is ready. He is ready to give his life to every act he is doing.”

Friends, if there is a message of Yom Kippur, it is that every act – every mitzvah – matters. We need to take agency for our spiritual lives; living intentionally, proudly and passionately as Jews. The fallbacks of the last seventy years no longer suffice. In order for Am Yisrael Chai, for the people of Israel to live, we must draw on the tools that date back to the very origins of our people – mitzvot. Me, I can only put the chicken on the table – it is your job to chew. One bite at a time, one mitzvah at a time. Let this year be the year for your Jewish spark to shine forth brightly for all the world to see.